When British used car company Cazoo floated on the New York Stock Exchange in 2021, it was worth a lofty $8bn, making it one of Europe’s highest-valued tech companies. But Cazoo’s unicorn days are long gone. Its share price has tumbled 99% since IPO and, today, its market cap stands at just $83m.

To try and bring the loss-making company’s share price in line, Cazoo announced a realignment plan in 2022: withdrawing from the EU entirely, laying off 1,500 people (around 30% of the workforce) and shedding some of its assets.

Cazoo’s founder, serial entrepreneur Alex Chesterman, stood down as CEO this month as part of the plan. Chesterman is one of the few people to make money from Cazoo: he reportedly cashed out £100m in shares in 2020 — a sum now worth more than the entire company — and was reported to have a net worth of £750m by the Sunday Times in 2021.

So what’s gone wrong at Cazoo — and what does its future hold?

The UK’s fastest-ever unicorn

Cazoo, which launched in December 2019, became the fastest-ever British unicorn when it hit a billion-dollar valuation in June 2020. It raked in more than £200m in its first 18 months of existence from big VCs like General Catalyst, Eight Roads, Molten, Mubadala Capital, Octopus Ventures, DMG Ventures and Stride, with promises to revolutionise a market worth £50bn+ in the UK alone.

“In 2003, every high street had a video shop; by 2008, none did. My hunch is that, with cars too, people will ask why they ever did it the old way,” Chesterman said in early 2020.

The company expanded fast in 2021 and early 2022, buying up competitors around Europe and launching operations across the continent.

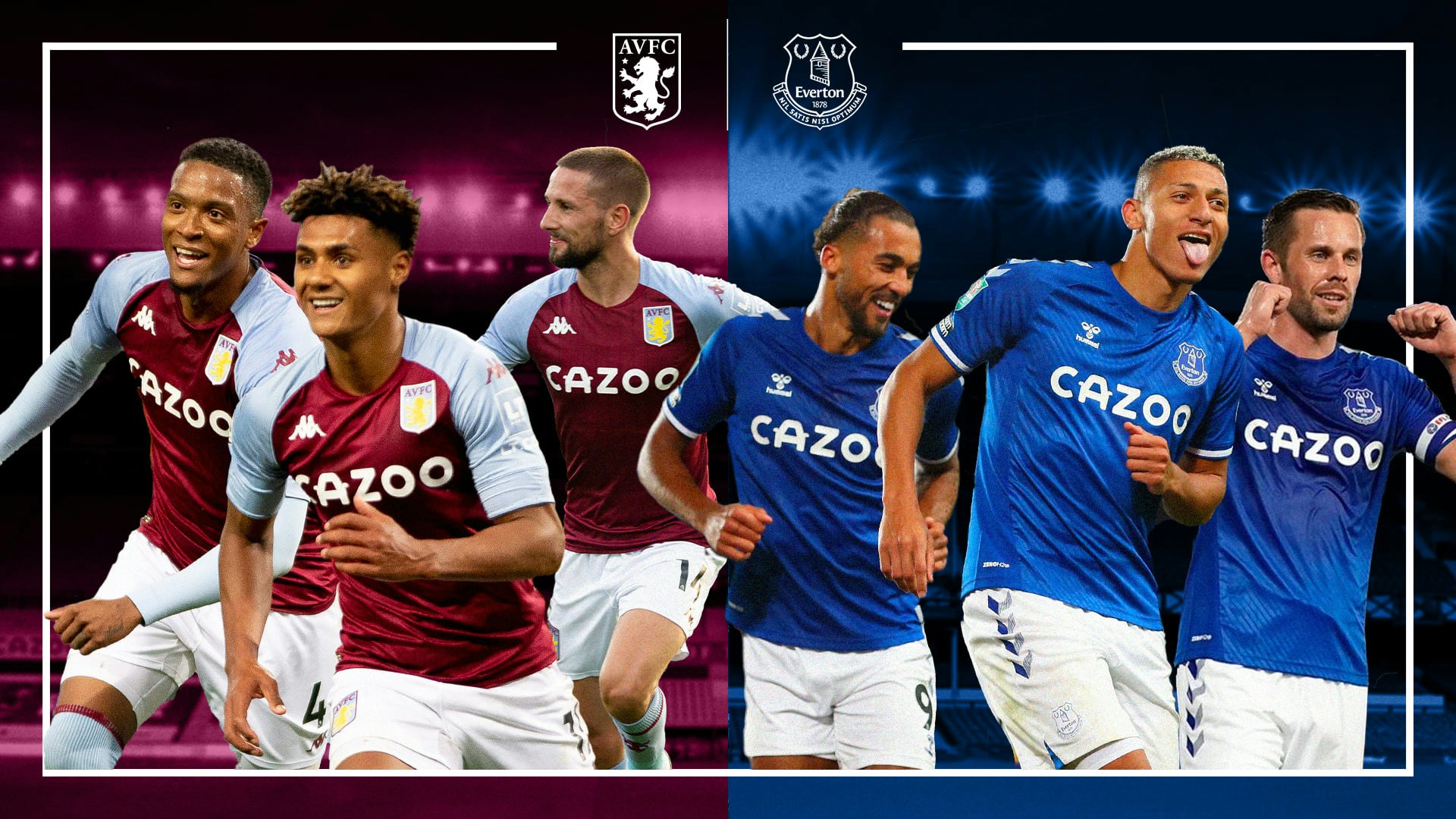

There was seemingly no sport it wouldn’t sponsor: rugby, snooker, golf, cricket and a host of football clubs, including Olympique de Marseille, Bologna FC, Everton and Aston Villa. When the latter two played each other last season, every footballer on the pitch had the Cazoo logo emblazoned on their shirt.

Tech was booming across the board, and investors were willing to splash the cash on big bets. SPACs — special purpose acquisition companies — were also all the rage, and Cazoo chose to list this way in August 2021, at an $8bn valuation.

Things started going downhill from there. 2022 was a turning point for the tech world. Rising inflation and interest rates has meant there’s less VC cash washing around — and public tech stocks have fallen across the board.

“The timing of their IPO was the worst in history,” says one investor who was close to the company back then.

Too much, too soon?

Cazoo is very similar to US company Carvana, which was founded in 2012 and valued at $65bn at its peak — it’s also seen its share price tumble. The success of Carvana meant that, during 2021 — a record-breaking year for tech investment in Europe — VCs were desperate to get onto Cazoo’s cap table.

“Every VC firm in the world was desperate to catch the next Carvana,” a source close to the company tells Sifted. “Cazoo didn’t know how to effectively invest the money they were given. They raised huge amounts of money at an extremely aggressive valuation which forced them to try for hypergrowth.”

Then, when funding dried up and tech stocks plummeted in 2022, “they hadn’t scaled up operations efficiently enough to keep pace with their expansion, driving big cost overruns,” the source adds. The company’s pace of expansion — four new countries in 2021 — assumed that venture capital funding would continue to be easy to access.

Two former employees Sifted spoke to agree that, while Cazoo was the victim of changing market conditions, the pace of its expansion in 2020-21 had been misjudged.

“Growth was way too fast,” one says. “They expanded to other markets too quickly; they should have had a stronger focus on the UK.” “They fell down on the aggressive expansion method,” the other says.

It’s important to note that Cazoo isn't alone in scaling back its expansion plans as economies have cooled — and it’s also far from alone in laying off employees.

Shareholder dynamics

Cazoo’s share price has trended downwards in the last year in line with other used car companies like Carvana and Vroom in the US. But beyond the business model and the market conditions, industry insiders tell Sifted there are other dynamics at work in Cazoo’s tumbling share price.

In February last year, Cazoo raised $630m in convertible notes — short-term debt which converts into equity at a later date if not repaid. The funding was led by Viking Global Investors, a Connecticut-based hedge fund, and included some money from existing Cazoo investors like Mubadala and Willoughby Capital. Viking owns $300m of the convertible notes — it declined Sifted’s request to comment.

According to SEC filings, Viking’s stake will equate to 7.3% of the company once the notes convert — making it the third-largest shareholder behind Chesterman and Matrix Capital, a UK-based investment fund.

“It's clear they were going to run out of money and had to take the Viking loan; without it I don’t think they’d be solvent,” a source close to Cazoo tells Sifted.

The problem with raising debt is that, if a company folds, the owners of the debt get paid back before other shareholders. That, investors tell Sifted, can reduce the attractiveness of the stock for other investors.

That said, Cazoo’s choice of a convertible note is not rare. Many startups raise them, as they don’t dilute shareholder equity until they convert into shares.

The debt could put Viking in a powerful position within the company. SEC filings show the fund has the right to have an observer attend all Cazoo board meetings.

The Daily Mail offloads its stake

The other shareholder dynamic at work within the Cazoo cap table is the stake previously held by British media company the Daily Mail and General Trust (DMGT), which also makes VC investments.

DMGT de-listed in 2021 after the controlling shareholder, the Rothermere family, won a bid to take the publisher private. When Rothermere bought out DMGT’s other shareholders it used the company’s Cazoo shares as part of the deal, according to DMGT filings, offloading its 17% share in Cazoo to DMGT’s shareholder base.

For every share owned in DMGT, shareholders were paid 0.5749 in Cazoo shares. Those shares have since lost 97% in value, leaving those who took them on looking at a nasty loss. DMGT did not respond to requests for comment.

The majority of Cazoo’s shareholders had been institutional investors making long-term bets. A portion of the shareholders DMGT transferred its stake to were retail investors — a group that's often less comfortable taking a long-term bet on a riskier company.

Underneath the hood: does the business model work?

But other investors say that investor dynamics aren’t as big a problem as Cazoo’s business model itself.

Cazoo acquires used cars from car traders and car owners, reconditioning them in refurbishment sites run by the company and then selling them on. Cazoo doesn’t own dealership sites like traditional used car businesses: it instead delivers the cars directly to customers.

In 2022, Cazoo sold a record number of cars: 65k. It also, according to financial statements, managed to up its gross profit per car (GPU) to £600, up from £488 in 2021. The company recently announced that it reached £900 GPU in the first two months of this year.

The catch is that gross profit doesn’t take into account the costs of the sale or refurbishment of the cars, or the marketing (all those football sponsorships). Cazoo still makes a net loss on each car.

In 2022, according to its financial filings, Cazoo made £1.3bn in revenue. From that, it made £20m gross profit. That figure doesn’t take into account £668m in operating losses, including £62m in marketing costs and £96m in sales and distribution costs. Overall, Cazoo made a £704m loss for 2022.

One VC investor who did not invest in Cazoo tells Sifted he thinks that’s where one of the central problems lies. Cazoo, he says, has replaced the costs of physical dealerships with other costs which have been, to date, higher than the costs incurred by the incumbents in the market.

“Cazoo has swapped the dealership network — the out-of-town, large-scale dealerships, and all the costs that are associated with that — for huge marketing, technology and delivery costs,” the investor says. “And in the sale of second-hand cars, you just can't afford to deliver cars to people’s doorsteps.”

Cazoo offers free collection when it picked up customers’ old cars, but it does now charge for delivery: £149 per car.

The used car market is not one ripe for tech disruption, the investor believes. It’s a low-margin industry and there are limited points where tech can actually help cut costs.

"You can't change the fundamental inputs of the majority of the P&L: which is, the cost of the cars they intend to sell on to customers. It’s a 10% gross margin industry where you buy a car for nine grand and sell it for ten. And technology can not and will not allow Cazoo to increase that, no matter how much they talk about disruption or tech.”

Scale is where Cazoo will be hoping to make its money — a lot of traditional car dealerships are local businesses, so Cazoo could tap into scale more easily as it's a nationwide company, other investors claim.

The make-or-break survival plan

In June last year, Cazoo’s “realignment plan” involves the sale of businesses Cazoo acquired during its expansion phase — such as car data platform Cazana and German startup Cluno. Sources close to the company tell Sifted that Cazoo is selling off the businesses it acquired for a fraction of what it bought them for.

The plan also includes reducing the number of cars sold to 40k-50k this year, to allow it to focus on, the company says, “higher margin and faster-moving inventory”. But it will also mean trying to find ways to streamline marketing and sales costs as well, investors say. Sifted understands that there are no more layoffs planned.

The company said it had £258m in cash and equivalents at the end of 2022. If its burn rate stayed the same this year to last year (£704m in 2022), Cazoo would have just months left in runway. But the realignment plan is forecast to reduce cash burn: Cazoo estimates it’ll end 2023 with at least £110m in the bank and not have to raise any more funding for the next 18-24 months.

Although Chesterman has stood down from his CEO role, he remains the company’s largest shareholder, with approximately 25% of shares.

The company’s also seen senior exits in recent weeks. Anne Wojcicki, an American entrepreneur who had sat on the board since early 2021, left, citing personal reasons. In August 2022, the company’s CFO also departed, replaced by Paul Woolf, who previously worked at Graphcore.

The company’s new CEO is Paul Whitehead, previously COO. Whitehead has been at the company since it launched — and worked with Chesterman at property platform Zoopla before that. He’s an experienced operator, but he takes the helm at a company with a floundering share price and a significant shift needed to bring its runway back in line.

Cazoo has already cut back on marketing, dropping most of its sport sponsorship deals. It curtailed its planned multi-year sponsorship deal with cricket tournament The Hundred after just two seasons. And as for Everton and Aston Villa, the two English football clubs who took part in the infamous "Cazoo derby" — Everton have a new sponsor and Cazoo's logo is set to disappear from Villa shirts at the end of this season.

Cazoo declined to comment.