To hit the Paris Agreement’s goals by the end of the century, the world will have to reach net zero greenhouse gas emissions.

While transitioning to renewable energy is a necessity, a new wave of startups are already developing methods to remove existing carbon from the atmosphere. Think nature-based solutions like carbon sinks, or technologies like direct air capture that capture, store and, in some cases, utilise carbon dioxide.

“We all depend on energy and we cannot build a new energy system fast enough. In the meantime we need to move to a net-zero carbon world where society achieves a balance between the greenhouse gases emitted and those taken out,” says Geert van de Wouw, managing director of Shell Ventures, the corporate venture capital (CVC) fund of energy company Shell. “So carbon capture has to be part of the solution in order to work out the maths.”

Startups and scaleups are at the forefront of carbon capture innovation, but how can they scale? We spoke to six startup finalists from the New Energy Challenge — a competition for European startups developing solutions for the energy transition jointly organised by Rockstart, Shell, Unknown Group and YES!Delft — that say they can.

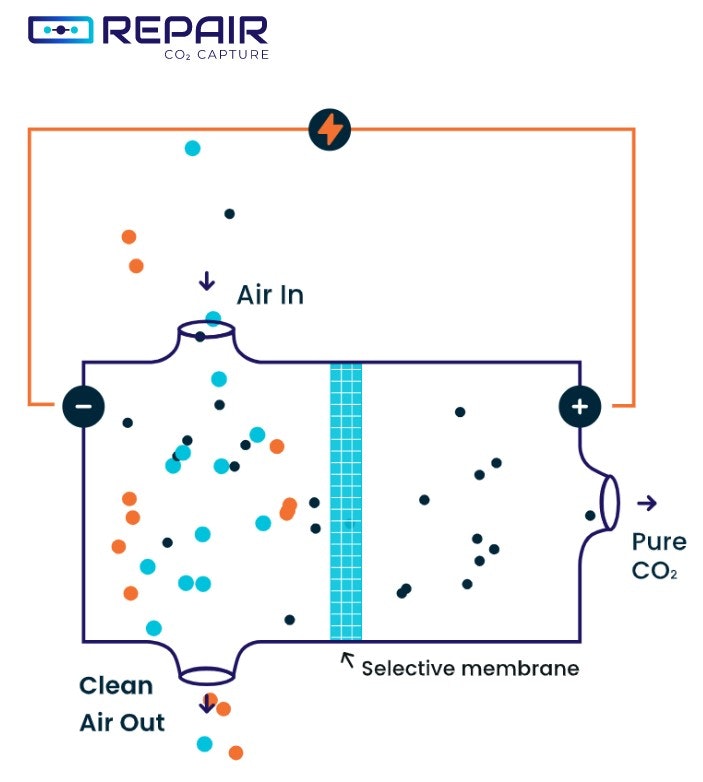

1. RepAir

One method of reducing CO2 is direct air capture, a technology that uses chemical reactions to pull carbon out of the air. There are two approaches — a liquid approach where air is passed through a chemical solution to remove the CO2 and a solid approach where filters chemically bind with CO2. However, it’s expensive and uses a lot of energy.

Israel-based RepAir uses an electrochemical-based instrument for its direct air capture. Naama Gluz, its research lead, says an advantage of its tech is its low energy consumption as it doesn’t require high temperatures or high pressure.

So far, RepAir has a validated lab prototype that it’s currently trying to scale. To store the carbon once it’s captured, it’s collaborating with other companies.

“We are moving from a lab of prototype size and then we can increase and scale up the electrode itself,” says Gluz. “You can take several electrodes and make a stack.”

2. Carbominer

Another capture technology is being built by Ukraine-based Carbominer, which uses a combination of the liquid and solid approaches explained above.

“The general idea was to leave a better world for my kids,” says Carbominer’s CEO Nick Oseyko. “We built our first machine last September, the first prototype.”

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, many of the startup’s team members have been displaced around the country or moved to Poland. But in early April, when Russian troops left northern Ukraine, Carbominer reunited its team in its Kyiv lab and resumed working.

“We want to do the pilot in October this year and with this pilot, the validation of our technology will be achieved,” he says. “It will help us to raise the next [funding] round, and we are going to establish a production facility in eastern Poland.”

3. Barton Blakeley Technologies

UK-based Barton Blakeley Technologies uses rocket technology to burn carbon dioxide and transform it into a solid material that can be used to make everyday products.

“If you think about the stuff that comes out of the bottom end of a rocket, that stuff is useful and it’s valuable,” says Zara Tunnicliffe, Barton Blakeley Technologies’ commercial manager. “Material can go into anything from paints to adhesives, even your clothing. It can be used as a hydrophobic coating.”

Right now, the startup is manufacturing material for a small number of clients, but Tunnicliffe says it can be scaled up using a “copy and paste format”.

She adds that the way we think about carbon has to change, because it’s not enough to just remove it and store it — it needs to be useful.

“If we actually convert it into something, repurpose it and treat it more like a resource, that’s going to be the way forward rather than simple sequestration,” says Tunnicliffe.

4. Novocarbo

One use of carbon is biochar, a solid material that can be used to build concrete, plastics or soil, and Germany-based Novocarbo is making it.

“Biochar is essentially just carbon,” says Venna Lepel, the startup’s chief commercial officer. “We take atmospheric carbon and we transform it through a process called pyrolysis into a stable form, in a solid form of carbon that looks like charcoal.”

While still under research, Lepel says biochar’s most promising use case involves soil.

“What is best researched is actually a function as a soil amendment,“ says Lepel. “It brings up the fertility of the soil and it prevents leaching [the loss of nutrients from the soil].”

Lepel adds that a significant hurdle is scalability but utilising carbon through different applications could alleviate that problem.

“It doesn’t make any sense to store biochar underground or put it somewhere in a mountain. We want to use it because we need carbon,” she says. “We want to keep the cycle going and really go into the circular economy.”

5. PYREG

Another biochar startup is Germany-based PYREG. Henriette zu Dohna, its PR and communications manager, says biochar’s highly porous structure means it has a water and nutrient uptake capacity of five times its own weight. This makes it good for use in agricultural applications.

“The low biodegradability of biochar ensures that it remains effective in the long term and can be considered a permanent carbon store,” she says, adding it can be used as a feed additive, bedding in barns or in manure treatment.

According to zu Dohna, “the PYREG technology is fully proven and commercialised,” and the startup will have 50 installations with a yearly CO2-equivalent sequestration capacity of 30k tonnes by the end of 2022.

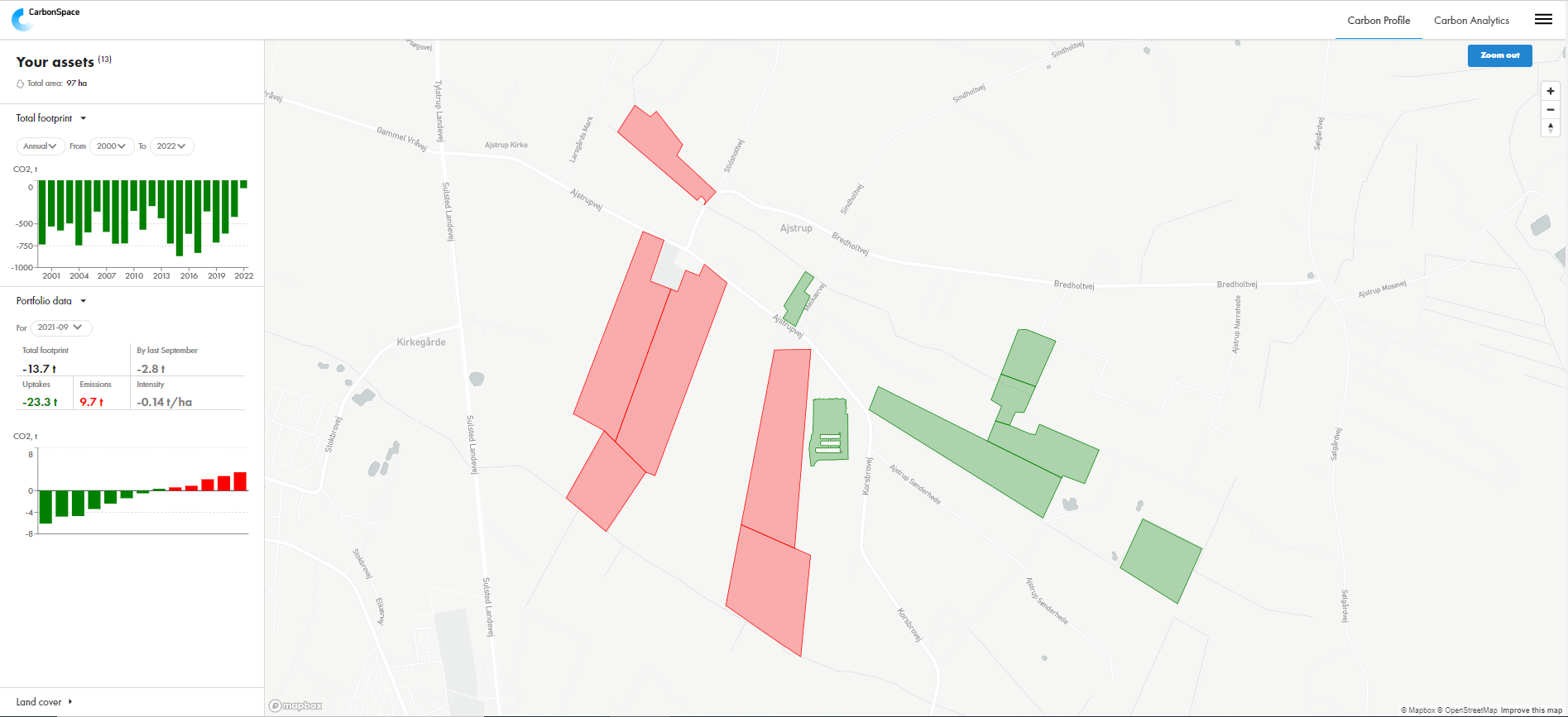

6. CarbonSpace

Another way to sequester carbon is by using nature-based solutions. For example, Ireland-based CarbonSpace has designed a satellite power tool that estimates the biospheric emissions and sequestration of carbon sinks.

“Corporate carbon accounting and nature-based projects require manual measurements from experts and third-party validation,” says Emma Fourdan, who is leading business development in EMEA. “It makes reliable estimations more complicated and almost unavailable to some customers because of the complexity.”

Because the technology relies on remote sensing and doesn’t require on-site operation, Fourdan says it’s easily scalable. She adds CarbonSpace has already estimated the carbon footprint of over 3m hectares of land.

“A lot of energy companies are investing in nature-based solutions,” says Fourdan. “Our goal is to guide effective climate action.”

If you want to learn more about these and the other NEC finalists and their journey, visit our website or follow us on Linkedin and Facebook.