It’s hard to miss the candy-pink posters that now adorn London streets and buses, sweetly declaring war on credit cards via the slogan: #WhyPayInterest.

Klarna, the Buy Now Pay Later (BNPL), is behind the marketing blitz, seeking to separate itself from nasty interest-charging credit cards and counter accusations of fuelling debt spirals.

It’s the most aggressive demarcation yet of the BNPL industry’s ambition to take on credit cards.

But does the success of BNPL spell doom for the $3tn credit card industry? A new report by Sifted Intelligence says that BNPL companies shouldn’t be so confident yet.

The credit card slayer

Credit cards were arguably the first ‘fintech’ phenomenon, allowing consumers to defer digital payments and then repay the debt in one lump sum. The catch was that late repayments came with double-digital interest charges, giving the big credit card providers — including Capital One, American Express and big banks — chunky revenues (the average US credit card holder pays $753.80 per year in charges).

But a decade later, Buy Now, Pay Later (BNPL) rose to become the new tech-driven star of ‘point-of-sale credit’, allowing users to instantly defer payment over various instalments at zero interest across millions of merchants. Instead of relying on user fees, BNPL companies instead took a cut per transaction from retailers.

Today, BNPL has proven to be an attractive alternative to credit cards; nearly £4 in every £100 spent online in the UK uses a BNPL product.

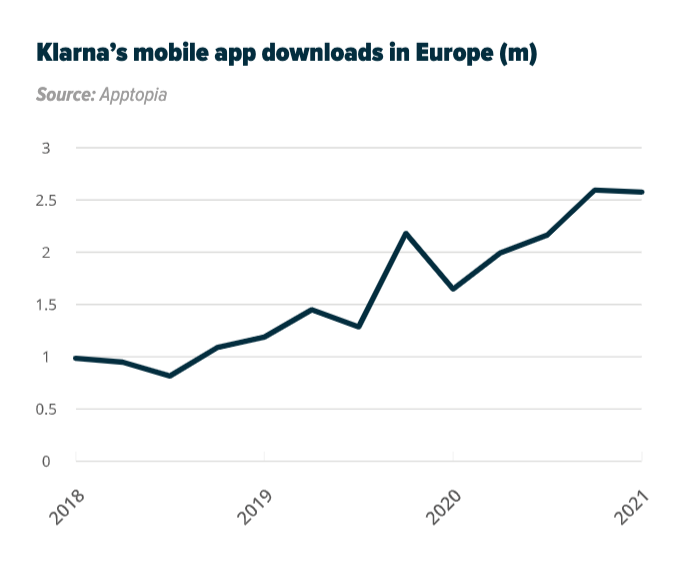

Throughout the pandemic, BNPL transactions saw both record user growth and record investment from VCs. In the last quarter of 2020 alone, Klarna saw over 4m downloads in the US, Apptopia shows.

And it’s not just Klarna. Across Europe, a series of contenders have popped up in the BNPL market.

Plenty of pie to go around

Klarna may have pitted itself against credit cards, but the two options aren’t mutually exclusive.

Take the example of Nigel Morris, the founder of Capital One, who also became an early investor in Klarna. Morris told Sifted he backed Klarna as an alternative, “largely complementary” credit facility to cards, rather than a competitor to his own company.

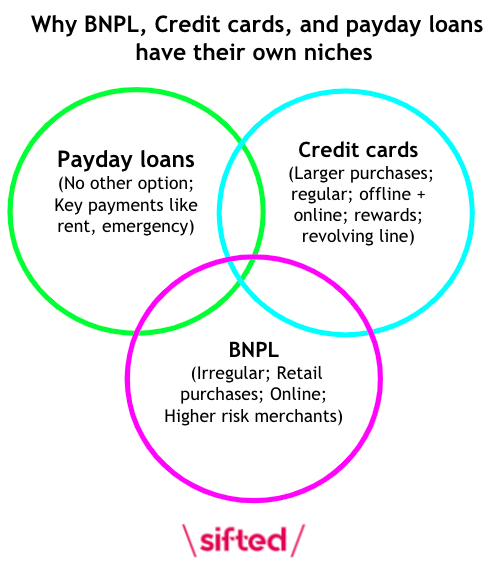

He explains that i) Klarna caters to a different income market than credit cards, and ii) that BNPL only concentrates on one key area of transactions (namely, retail).

The potential for cross over between the two, and their cousin in payday loans, looks something like the diagram below:

In other words, there’s enough of the pie to go round.

So, credit cards aren’t for everyone — or for every transaction — meaning BNPL can exist without directly taking market share.

For instance, one US study showed that 14% of BNPL users weren’t eligible for a credit card anyway. Meanwhile, almost 50% of Americans in their 20s don’t have a credit card, and just 33.7% of European adults have credit cards. That leaves a big credit card-free audience that BNPL providers can absorb.

BNPL arguably targets a wider demographic too, by allowing consumers to pay back in various chunks rather than a rigid one-month cycle.

For those who can afford them, credit cards still continue to lure customers with perks and convenience. Rewards packages are tempting hooks, as are the payment protection schemes they offer on larger transactions.

Having said that, there is some crossover. Indeed, credit card companies will want to hold on to the 33.7% of cardholders as tightly as possible and avoid being replaced by BNPL providers

A 2019 Deloitte report stressed that BNPL had irreversibly taken some market share from credit cards. It also argued that card issuers will need to innovate, unbundle and “modularise” to keep pace.

Yet Deloitte researchers also stressed that BNPL will reach a peak.

“There will eventually be limits to its growth, as consumers realise the tradeoff between flexibility and control, lenders struggle to extend their low-touch credit scoring for online [point of sale] POS finance to higher ticket items, and some existing products adapt to mimic features of POS finance,” the report said.

The credit card will remain an important product due to its distinctive ability to combine the supply of credit with a payment device

In short, Deloitte argued that credit cards aren’t going anywhere and that the market needs both. “The credit card will remain an important product due to its distinctive ability to combine the supply of credit with a payment device,” the report summarised.

BNPL and credit card chimaeras

One key trend is the blurring of BNPL and credit card models.

A key example here is UK player Zilch, which dubs itself “the American Express for millennials and Gen Z”, offering a card with a personalised credit line which is then paid back in instalments.

The idea is to be less cumbersome than BNPL, says Zilch’s CEO and founder Philip Belamant, pointing to issues like credit being denied at checkout or not having your BNPL of choice available at every merchant.

“BNPL has been built for retailers, not the customer,” Belamant tells Sifted. “We wanted to make it customer first and retailer second… You don’t have to worry about getting rejected at the very end now — and you can shop anywhere.”

Having a single card also saves consumers from handling multiple BNPL providers, including Afterpay, Clearpay and France’s Alma.

Meanwhile, Klarna and Affirm also both launched ‘one-time’ disposable card products. That allows users to plug in a card number and then pay it back in instalments. Fellow UK player Tymit has also followed suit.

“Instalment credit cards are a new emerging genre,” says Tymit’s chief executive Martin Magnone, adding that Tymit would cancel out the need for BNPL but that “killing the credit card entirely is not the answer”.

Traditional credit card companies are jumping onto the instalment model too. American Express, for instance, has launched a hybrid model in the US called Pay It Plan It, which gives users the choice of paying small transactions instantly, lowering their monthly debt while still accumulating ‘points’.

The basic idea here is to grow the parts of the Venn diagram they can attack.

BNPL’s Achilles heel

BNPL providers may be disruptors, but they are not immune to disruption themselves.

Many are heavily reliant on a small handful of merchants, having onboarded them individually as a shortcut to reaching thousands of consumers. Affirm, for example, makes around 28% of its revenues from just one client, Peloton. If they lose them, they’ll really feel it.

Meanwhile, Amazon is a big client for Klarna in the US, but it could well launch its own instalment payment system. While that would first require technological investment and ‘debt collection’ hassle, it’s not impossible and would again be a blow.

Meanwhile, Australia’s Commonwealth Bank has announced its own in-house BNPL product for account holders. Despite having invested in Klarna, it’s now looking to undercut them (a so-called 'race to the bottom') and could lead to a handful of casualties in the Australian market.

These vulnerabilities have raised questions among some investors. It’s also why large European VC funds like Index Ventures haven’t invested in the space, because they are sceptical of how ‘techy’ BNPL really is.

Perhaps then, it’s not just credit card companies who need to worry — it’s also the BNPL squad.

To read more about Europe’s payments revolution, check out our report. Download it here.