Anyone needing a shot of positivity following this dispiriting Covid-plagued year should jump on a Zoom call with Benedict Evans. The fast-talking tech analyst, who last year returned to the UK after five years with Andreessen Horowitz on the West Coast, is fizzing with the conviction that tech is going to change pretty much everything in our world as smartphones have become ubiquitous.

“I am optimistic about tech and I’m optimistic about European tech,” he says in a video interview.

After joining London-based Mosaic as a venture partner in January, Evans has just produced his latest 60-slide presentation entitled Europe, Unicorns and Global Tech Diffusion, in which he calls the end of the American internet, the globalisation of the Silicon Valley startup model and the rise of the rest of the world. “Tech is now part of everybody’s life and every business,” he says.

In his view, the internet, software and consumer technology have reached the same point as the car industry did when it became a commonplace means of transport. “There is a saying that the first 50 years in the car industry were about creating car companies. The second 50 years were what happened when everybody had cars. You create McDonald's and Walmart and everything else.”

“We have finally got to the point when everyone has a computer. So what now? And the answer is: everything else. There is a huge amount of creation that happens in Europe. You don’t have to be in that Silicon Valley cluster any more.”

Here are five of the main insights from his report:

1) It’s not all about Silicon Valley

There was a time when the computer industry was overwhelmingly concentrated in Silicon Valley. When Apple launched the Mac in 1984, global PC unit sales were about 6.5m units. Now there are an estimated 3.5bn smartphones across the world.

Startup companies have sprung in every continent and the venture capital industry has gone global. “A Silicon Valley company is an invention in its own right, just as the limited company was. And that invention has spread globally in the past 10 years,” he says.

That has meant that the gravitational pull of Silicon Valley has diminished just as rocketing house prices have forced many ambitious startup entrepreneurs out of the Bay Area. “You don’t have to physically be there anymore,” he says. That diffusion trend may only accelerate as people become accustomed to remote working thanks to the pandemic.

2) There are a lot of smart entrepreneurs in Europe

One of the things that struck Evans after returning from California was how far it had become normalised to launch a startup in Europe, which was certainly not the case when he graduated in 1998.

“There used to be a joke that there were only three American books: Moby Dick, The Great Gatsby and Catcher in the Rye. Similarly, there were only ever three startups in Europe: Skype, Spotify and TransferWise,” he says.

“There is both a sense of Silicon Valley being incredibly overheated as we see in the valuations but also a sense that there are a lot of interesting good tech companies coming out of Europe now.”

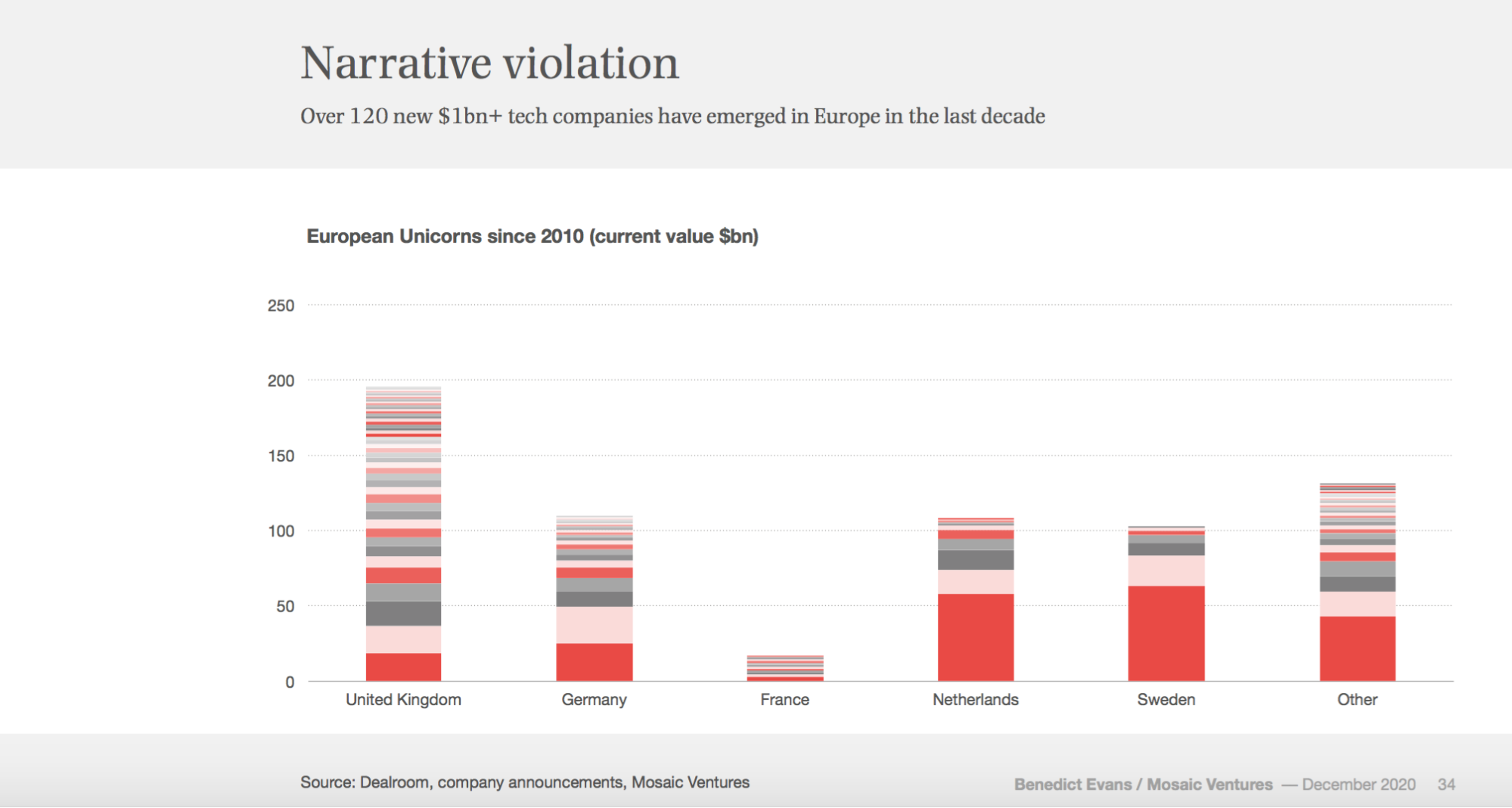

As his report notes, there is a higher proportion of STEM graduates in Europe than in the US and Europe accounts for seven of the top 20 computer science departments in the world — Oxford, ETH Zurich, Cambridge, Imperial, TU Munich, UCL and EPFL. Company creation is also similar to the US. More than 120 unicorns, collectively worth in excess of $600bn, have emerged in Europe over the past decade.

3) The VC industry has grown up in Europe

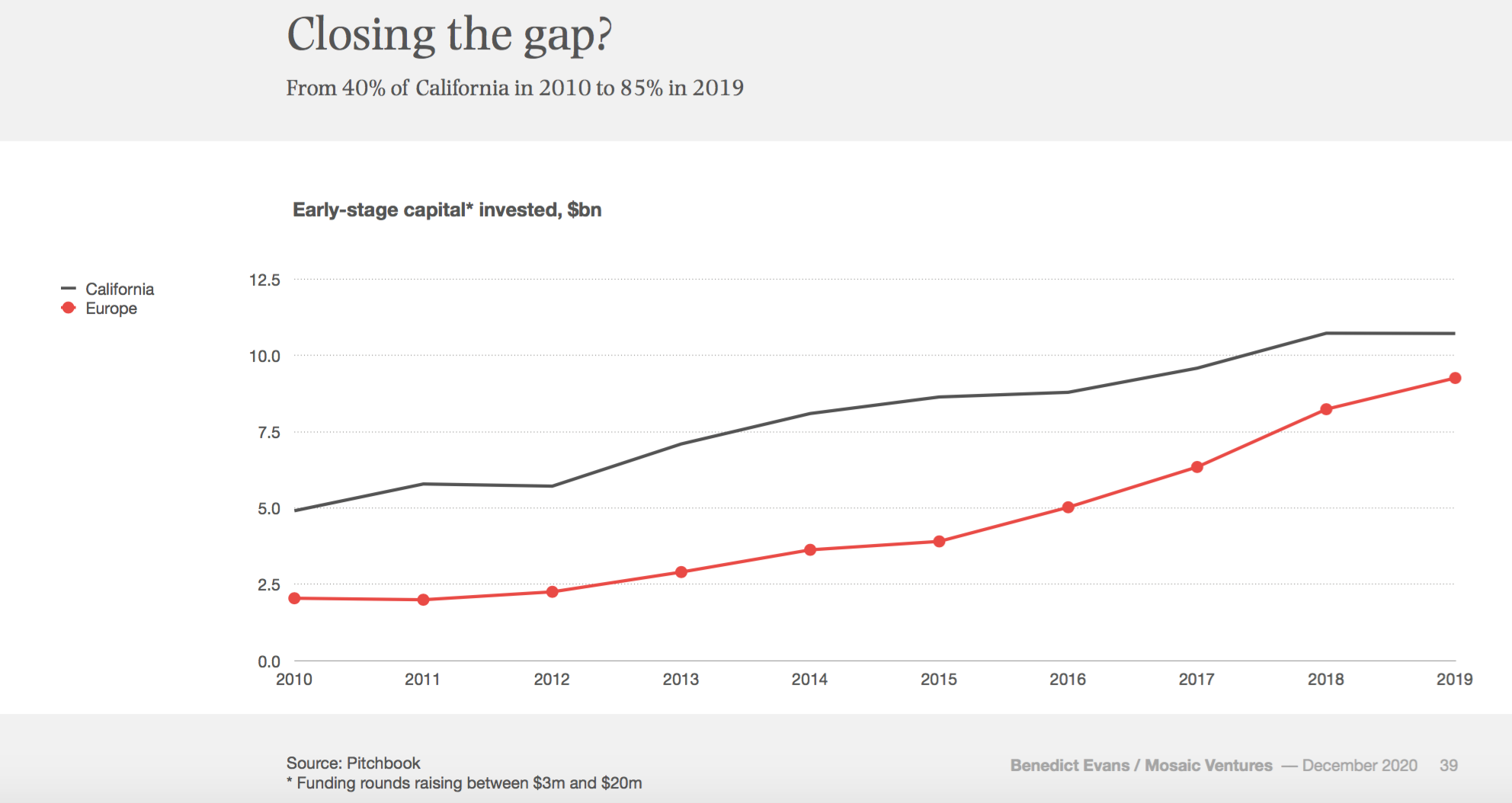

Europe may have lagged well behind the US and China in terms of VC funding over the past decade, but it is closing the gap. Early stage funding in Europe has increased four times since 2010, spreading into many more areas beyond fintech and biotech. Growing US VC interest in Europe has been highlighted by Sequoia’s decision to open a European office.

But it will take time for this early-stage investment to turn into world-beating tech companies. “The paradox of venture is that you’re dealing with this incredibly fast transformation and it’s a get-rich-slowly business when the average IPO is eight years,” Evans says.

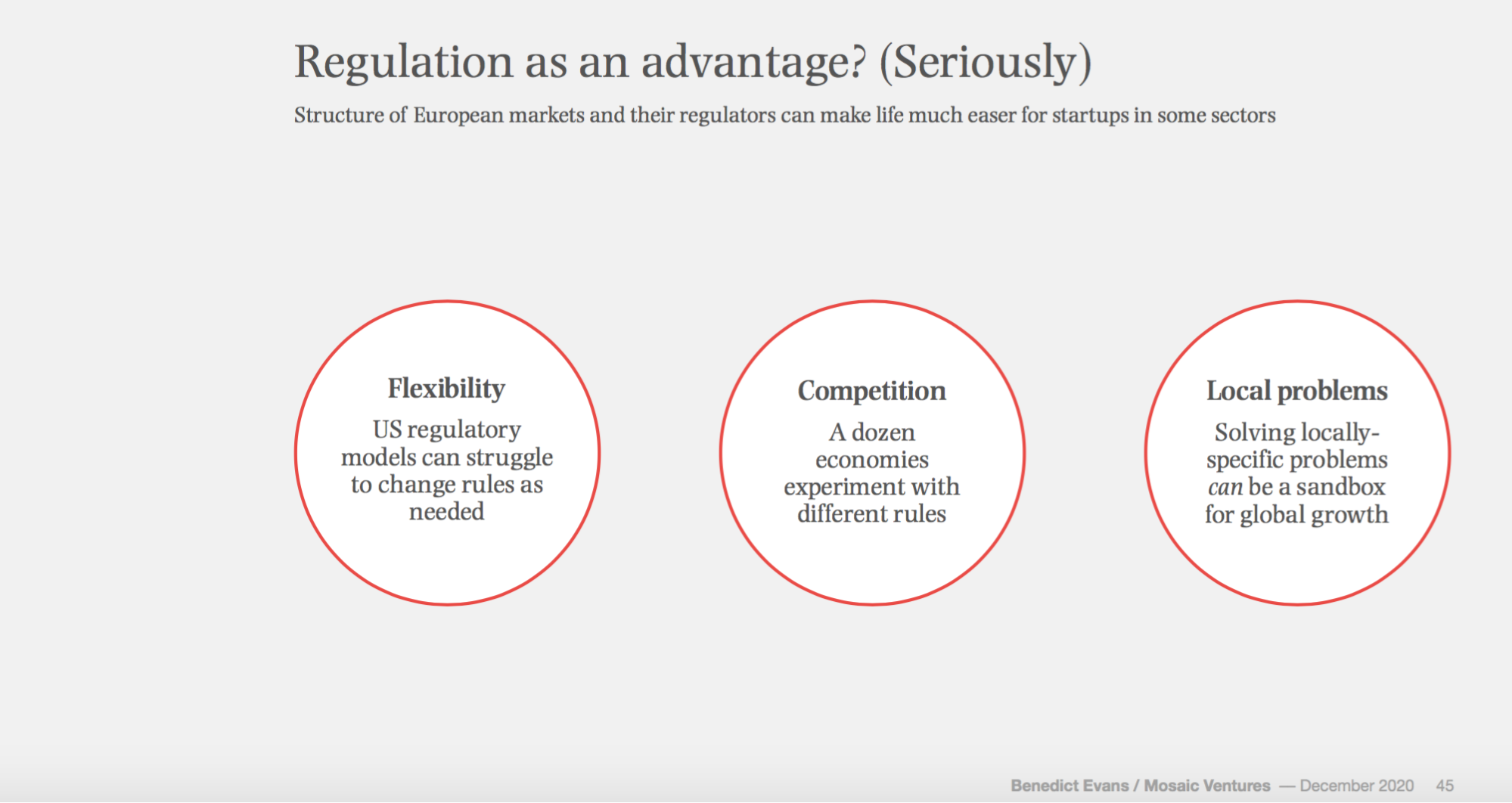

4) Regulation may be a source of competitive advantage for Europe

US tech titans may argue that excessive European regulation only protects incumbents and stifles innovation. But Evans says that in some respects Europe has a more flexible regulatory regime than the US (eg. the use of drones) that could be more welcoming for tech startups. “There is a class of regulatory questions where it is very difficult to change things in the US. It can be easier to change things in Europe,” he says.

“I remember a conversation we had at Andreessen Horowitz with a British cabinet minister and one of our general partners said it would be good if you could change that law but of course you can’t. And the cabinet minister said: ‘What do you mean we can’t change the law? We’re the fucking government. It is the only thing we can do.’”

How Brexit will change this equation is as yet unclear. Evans says the disappearance of the British counterweight within the EU may result in Brussels turning more protectionist. But it is also possible that any regulatory divergence by Britain could lead to a more competitive dynamic within Europe leading to the reform of outdated tax and option laws.

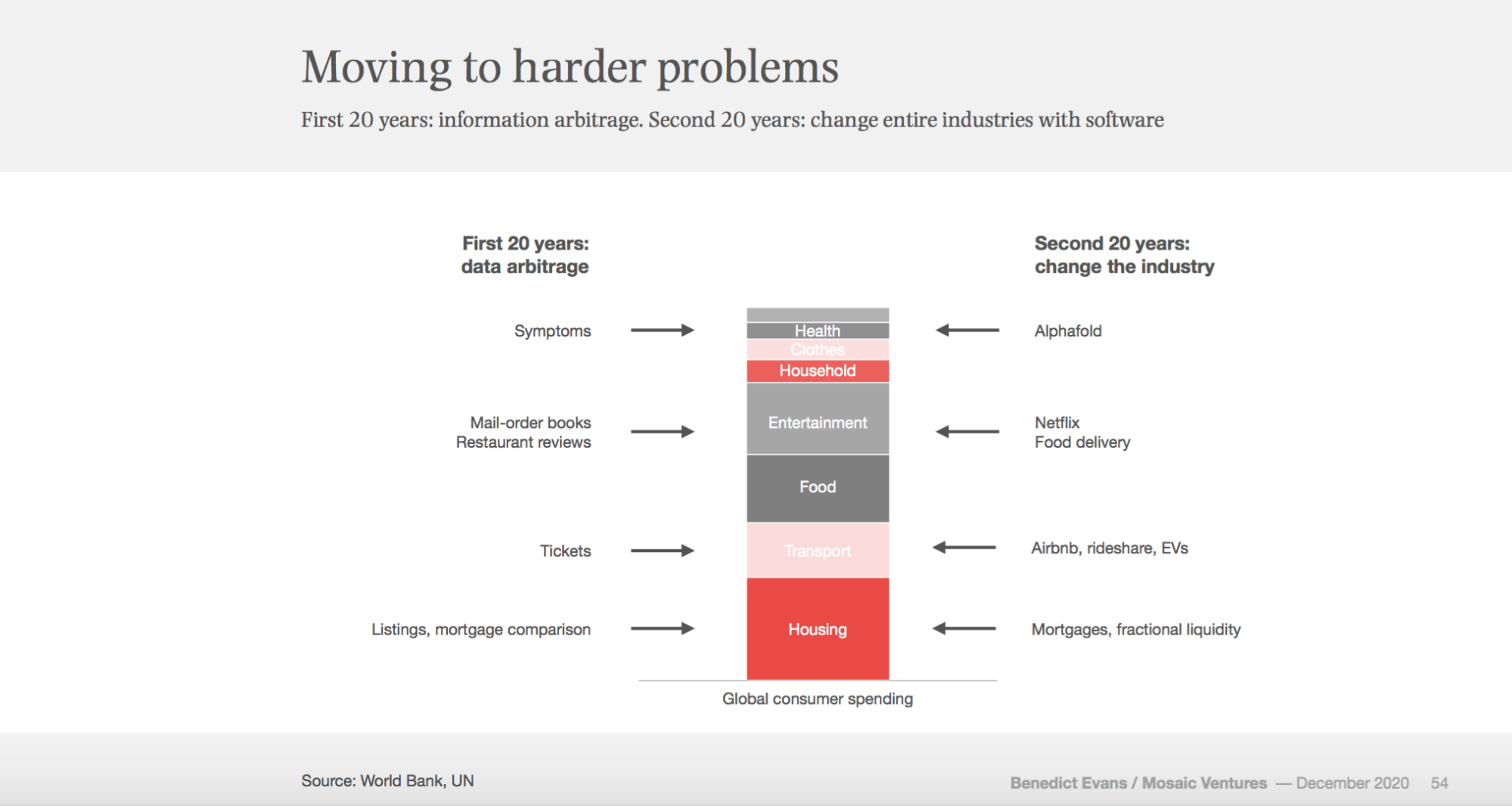

5) It’s all to play for

The US and China may have dominated the consumer internet market, leading to the creation of tech giants, such as Apple, Amazon, Google, Alibaba and Tencent. But the next stage of the tech revolution will impact every industry, creating massive new opportunities to transform existing businesses and build new companies.

“Nobody is going to start a Silicon Valley company to make marine engines. But the way they cast that metal will be transformed by software, the way they design the system will be transformed by software, all the telemetry and the way they manage it will be transformed by software,” says Evans.

“There was a point in time when all software companies were made in Silicon Valley and that’s ending because everyone can now create this stuff.”