It is a stealthy disease that countries have been trying to stall with quarantines. As it spreads inexorably around the world, it’s proving devastating to national economies. No, this is not Covid-19, but its banana equivalent: TR4, also known as Panama disease, which is threatening to wipe out our favourite yellow-skinned fruit.

Supermarket shelves may still be stocked chock-full of bananas, but the industry is growing increasingly alarmed. The fungal disease, which causes banana plants to wilt and die, has already devastated farms across Taiwan, the Philippines and Australia. Once in the soil, it can take 50 years to eradicate. Last year it reached the big banana farms of Latin America, which export the majority of the world’s bananas.

We really can’t do this fast enough. With Panama disease now hitting Latin America, it is going to have a big impact in the next 5 to 10 years.

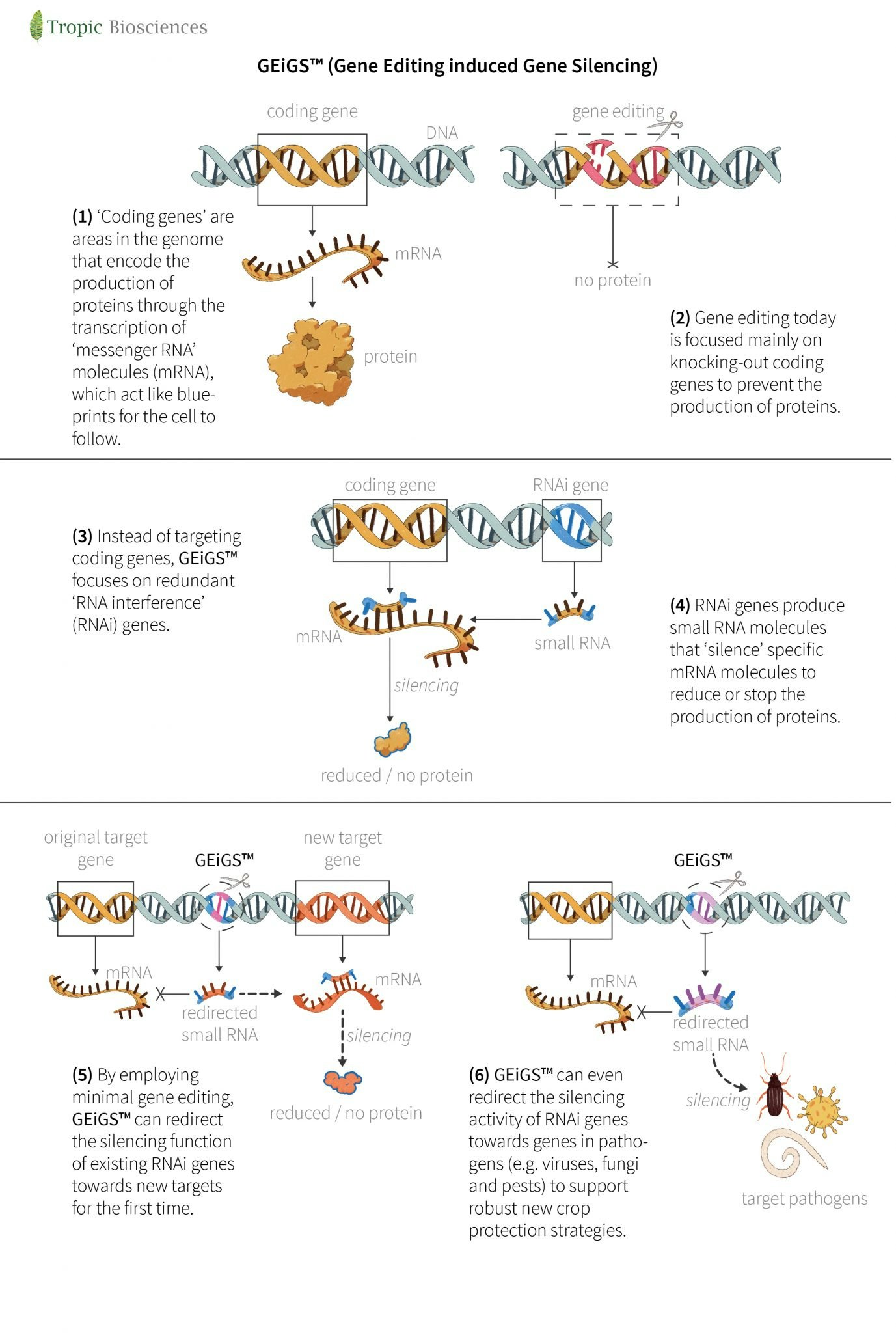

The race is on to find a cure for Panama disease or to breed a banana that is resistant to it. A new entrant into this effort is Tropic Biosciences, a UK-based biotech company, that is using gene editing to develop a banana that can beat the disease.

“We really can’t do this fast enough. With Panama disease now hitting Latin America, it is going to have a big impact in the next 5 to 10 years,” says Gilad Gershon, the company’s chief executive.

Getting out the big guns

Tropic Biosciences has a big team working on the banana. Out of around 70 people worldwide working on banana genetics, 60 of them work at Tropic Biosciences says Gershon. The rest tend to be in university research departments. Wageningen University in the Netherlands, for example, has a famous banana research programme. But Tropic Biosciences is one of the first to turn its banana research into a commercial proposition at scale.

Tropic Biosciences recently raised a $28.5m series B funding round, from investors including Temasek, the Singapore-based investment company, and Sumitomo Corporation Europe. Sumitomo owns the Ffyfes banana brand, so it is easy to see why they have an interest in the startup.

The first gene edited bananas plants could be in use in five years.

The idea that the familiar banana may disappear from our shopping baskets may seem ludicrous, but it has happened before. Up to the 1950s, the most commonly exported banana was the Gros Michel variety, which had sweeter flesh and thicker skin, making it easier to ship without bruising. But Gros Michel was wiped out by a strain of Panama disease, and growers had to scramble to find a new variety — the blander and thinner-skinned Cavendish banana that we are familiar with today.

This strategy worked well for 40 years. And then in the 1990s, a new strain of Panama disease was back, this time killing off Cavendish bananas. Because commercially grown bananas are all clones of the same plant, they are highly vulnerable to diseases, and it is hard to breed them for resistance.

There are some efforts to do this — a group in Taiwan, for example, is picking out and breeding Cavendish banana plants that are showing signs of some resistance. But genetic modification may offer a quicker route for an industry that is rapidly running out of time.

Tropic Biosciences — which also looks at improving robusta coffee beans and rice — has been working on banana genetics since 2017 and started with what Gershon refers to as (no pun intended) low-hanging fruit: extending its shelf-life and reducing browning. But in 2018 it began to tackle the big threat of Panama disease.

Now some of the first young plants, which have been modified with the Crispr gene-editing tool, are being grown at the company’s laboratory in Norwich, and also tested in fields already infected with Panama disease. The first plants developed in this way could begin to see widespread use in five years, says Gershon, if all goes well.

Is gene editing the right strategy?

Gene edited bananas may not be to everyone’s taste, however. Consumers in Europe have been fairly hostile to genetically modified food, and regulators will need to be convinced. Even if these hurdles are overcome, some scientists believe that gene editing is just a quick fix but does not get to the heart of the problem.

Dan Bebber, a professor of ecology at the University of Exeter, who leads a project, BananEx which is exploring the resilience of banana supply chains, says if we are to prevent agricultural pandemics like this, we will have to change the way we farm, becoming less reliant on clones and monoculture crops.

Fernando Garcia Bastida, a Wageningen university researcher who now works for KeyGene, a Dutch plant science company, would also like to see more varieties of bananas being farmed. There are hundreds of different varieties available in places like India and Indonesia, from the raspberry-flavoured Red Dwarf to vanilla-flavoured blue Java. The problem is that none of these has so far bred to withstand long haul transport like the Cavendish.

Gershon says he hopes more candid conversations about gene editing may help to alleviate some public fears. Overhauling the whole banana farming ecosystem may be a laudable aim. But given the urgency of the banana problem, he believes consumers and regulators may well find they have an appetite to try quick fixes too.