Balderton, one of Europe’s most active venture capital firms, is raising money for a new growth fund to plug a financing gap in the European market and take early stage startups through to public listings.

“We feel there is a massive opportunity here,” said Bernard Liautaud, Balderton’s managing partner, in an interview with Sifted. “What is interesting is the ability to support a company all the way from Series A to IPO. Right now we only support a company in the early stages.”

Balderton, which has invested in more than 200 early stage companies over the past 20 years, is aiming to raise hundreds of millions of dollars from investors giving it the firepower to help promising startups expand more aggressively. Although there had been a big influx of capital into early stage investment in recent years, Liautaud said, Europe still lacked sufficient growth capital to build dominant global businesses, such as Google and Facebook.

“We are going to help these companies grow much faster than a regular company. It may not be super efficient at the beginning. But the momentum that it creates and the ability to grow at speed is part of the recipe of success,” he said.

Money was an essential part of this “blitzscaling” methodology — as it has been called by Reid Hoffman, Linkedin’s founder and VC investor — but a different mindset was also necessary, he said. “Risk taking is critical to create massive companies. We have this in our DNA at Balderton because a number of us have worked in Silicon Valley and seen that model work. But it doesn’t exist in many other financial outfits in Europe yet.”

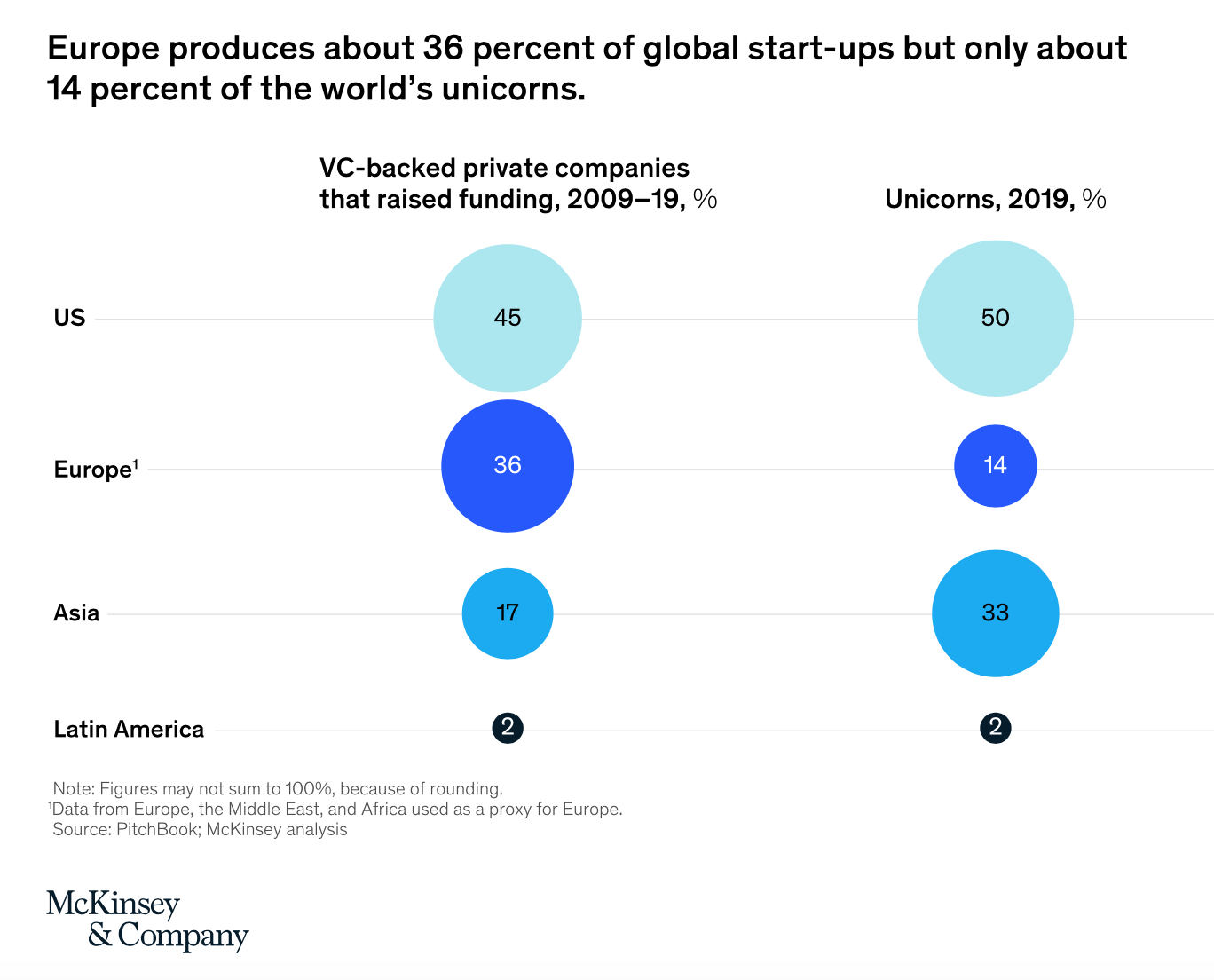

Europe’s inability to convert many promising startups into dominant global tech businesses is highlighted in a new report this week from McKinsey. Although Europe accounted for 36% of all global startups launched between 2009-19 it had only built 14% of the world’s unicorns in 2019. “Historically, Europe’s ecosystem has been less effective than that of the US at turning startups into late-stage successes,” the report concluded.

Liautaud, who floated his own enterprise software company Business Objects on Nasdaq in 1994, said that he had been disappointed that more European tech businesses had not emerged over the following two decades. The next French company to list on Nasdaq was Criteo almost 20 years later.

But he said that the European ecosystem had developed strongly over the past five years with the emergence of Spotify, Adyen and Farfetch. On a five and 10-year views, European returns were now matching, if not exceeding, those in the US. “We are big believers in Europe at Balderton,” he said.

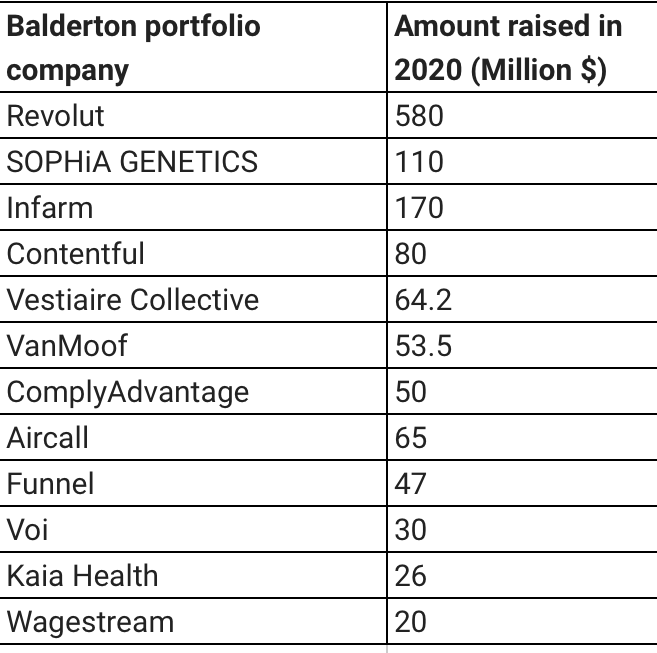

Balderton was a sizable investor in The Hut Group, the Manchester-based online retailer that listed on the London Stock Exchange last month at a valuation of £5.4bn. Liautaud highlighted Revolut, Vestiaire Collective, and Sophia Genetics as three of Balderton’s current portfolio companies that were now emerging strongly. “Most of these companies will have acquisition offers. But we need them to hang on and say we can go all the way,” he said.

While an acquisition was the end of the story, an IPO was just the beginning. “We need to have more companies that can go public and can go public in Europe.”

One of the issues highlighted by Liautaud was that institutional investors in Europe tended to be more prudent than their US counterparts and wanted companies to reach profitability much earlier. US investors were prepared to sink billions into companies like Uber enabling them to reach global scale, leaving European investors shaking their heads. “The world is big. If you want European companies to conquer the world really rapidly and do Asia and do the US and keep growing at 100% then you have to finance it. We have to constantly update our model,” he said.

By the year end, about 200 US companies, including Snowflake and Palantir, will have IPO’d in a bubbly tech market, while European listings have lagged a long way behind. But Liautaud insisted that a pipeline of interesting European companies was emerging. “The big difference now is that in virtually every European city there are seed funds, incubators, venture funds for Series A. You will see young entrepreneurs with a lot more ambition.”

In spite of the coronavirus crisis, Balderton’s portfolio companies have raised $1.8bn so far this year (see table), compared with $1.2bn last year. The firm has also made 15 investments in 2020, including 5 companies led by women.

But Liautaud acknowledged that Balderton had further to go in promoting diversity within its own firm. Only one of its 9 investment partners is female, although the firm has committed to ensuring gender parity in all future appointments. He said Balderton was now looking at a wider pool of companies in which to invest and was pressing all its portfolio companies to focus on environmental, societal and corporate governance issues.

“In the past, ethics has been seen as something of an impediment to business. But we think it is a great opportunity,” he said.

This story has been changed to reflect that fact that Balderton has invested in more than 200 early stage companies over the past 20 years, not 100 as originally stated.