Investors wouldn’t touch condom and lube startup Hanx when it launched in 2017, says cofounder and CEO Farah Kabir. But six years on, she says there’s been a “sea of change” in investor interest.

Considering the size of the opportunity, there’s little wonder why. In 2021, the global sexual wellness market was valued at $80bn — and it’s predicted to hit $120bn by 2030 — while sex toy sales continue to rise each year.

That’s driven by changing attitudes in society towards sex. In the US, 84% of adults now say that masturbation is a form of self-care, according to one report, and mentions of “sexual wellness” grew 600% on Twitter between 2018 and 2021.

So far, so good, right? Except that investor interest hasn’t translated into serious cash on the table. Over the past two years in Europe, sextechs have raised just £232m, according to Dealroom — less than a third of the funds pet tech startups have picked up, despite the sextech market being worth four times as much.

“The lack of funding has definitely held us back,” says Kabir, who has now raised $1.8m. “There’s lots of talk about backing sextechs from VCs, and change is coming, but that hasn’t yet turned into committed capital.”

So what’s stopping investors from putting their money where their mouth is?

Vice clauses and angels

One reason is “vice clauses” — restrictions set by LPs (the folks that invest in VCs) on where their money can be invested. They often cover things like tobacco, guns — and sex.

“We were hitting a brick wall with VCs and we had comments like ‘our LPs would never back something in the adult industry’,” says Kabir. “You can’t negotiate with the ‘LPs won’t back it’ line.”

Jens Petter Wilhelmsen faced the same issues when he was raising for his sex toy startup Handy, which makes a male masturbator and has picked up $2.3m in funding.

VCs and their institutional investors see vice categories as risky, he says, because there are some bad actors in the space. “Instead of risking headlines like: ‘this VC made 10x returns on a porn company that mistreats its employees’, they just avoid the whole sector.”

As a result, there are no VCs on either Hanx or Handy’s cap tables; they’ve mostly raised from angel investors.

Angels can bring great connections and invaluable industry experience, Kabir says, but VCs can dole out far bigger tickets and offer more help with scaling and expansion.

Wilhelmsen also thinks VCs' unwillingness to get into bed with Handy has put the brakes on progress. “With a company of our size, with the traction we’ve had, we would probably have raised 10 times the amount we have if we weren't a sextech.” Wilhelmsen says the startup had 1m sessions in December and that figure is growing 40% quarter on quarter.

Not all VCs are prudes

But some VCs aren’t turned off by sextech.

Charlotte Schofield, venture director at London-based Access VC, has backed a number of intimate wellness brands and is actively looking for deals in the sextech space. Access VC is more open to sextech startups than others because it’s the venture arm of consumer goods company Reckitt, which owns brands like condom company Durex and lube company KY, Schofield tells Sifted.

That gives Access VC a head start, she says, but among lots of VCs, there’s a real misunderstanding about the size of the market and the size of the impact.

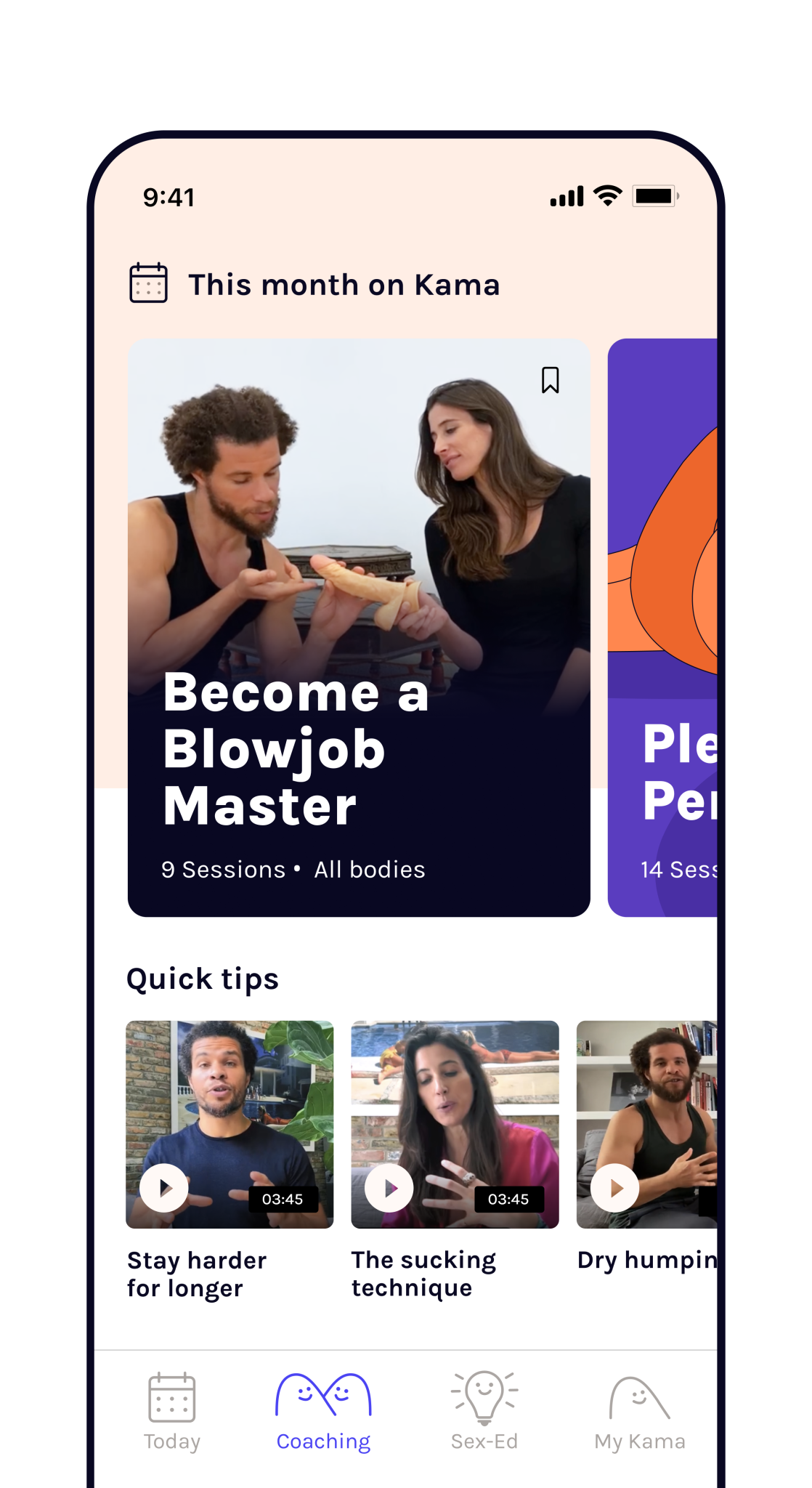

Covid lockdowns saw a massive surge in consumers using sextech apps and products — and this has continued post-pandemic. Alongside the uptick in usage seen at Handy, sex education platform Kama launched a paid version of its app in December and has seen 100k downloads in the past six weeks. Hanx has nearly tripled its direct-to-consumer sales since Covid, its revenues are growing 146% year-on-year and its condoms and lube are now in 2,500 high street supermarkets and pharmacies — a 25% increase since last year.

A small number of VCs in Europe are responding to the hype.

Austria’s Calm/Storm Ventures invested in companies like contraception-review platform The Lowdown — alongside Speedinvest and Nina Capital — last year, the LGBTQ+ sexual wellness platform Lvndr the year before and sex therapy app Blueheart in 2020. Sex party company Killing Kittens raised £3m in 2021 from Pario Ventures. Kama got backing from Stride.VC in its €3m seed round, also in 2020. The same year audio erotica platform Emjoy also raised €3m from Spanish VCs Nauta Capital and JME Ventures.

But funding for sextechs is still really low in Europe. While period tracking apps like Flo and Clue — which raised $50m and €16m in 2021, respectively — have picked up the most investor cash, around the €3m mark seems to be the cutoff for startups that predominantly cater to the pleasure side of sex.

That’s because sextech feels “new and uncomfortable” to VCs, says Angus Barge, founder of London-based erectile dysfunction startup Mojo. It’s raised €3.75m from a mixture of VCs and angels, including Kindred Capital and Octopus Ventures.

Barge found it “really challenging” to raise from VCs when the company launched in 2019, but says once you’ve built a business model that works you get VCs knocking on your door. “We’re just at the beginning. VCs are money people — if you can show them good numbers they’re interested.”

US sextech

Across the Atlantic, the sextech market is more mature.

Intimate wellness brand Hims & Hers has raised $272m and IPO’d at the start of 2021, at a $1.6bn valuation. Contraception company The Pill Club has raised $107m. Sexual wellness platform Cake has picked up $13.4m and sex toy startup Dame $11m. They’ve all raised mostly from VCs.

Specialist sextech VCs, like Amboy Street Ventures and Vice Ventures, have also emerged. While neither has backed a European sextech yet, Amboy Street Ventures has a London-based European partner, Dominnique Karetsos.

The lack of funding options in Europe has led Kabir to look to the US when Hanx goes out to fundraise a £3m round later this year. “UK VCs are still not prepared for sextech and the US is a few years ahead.”

Embarrassed investors

Many VCs are still uncomfortable talking about sex because it’s such a taboo in wider society, says Schofield.

“Founders need to equip the investors they are pitching to with the right terminology, because often there’s a barrier where people get worried about making a mistake when they’re talking about the subject,” she tells Sifted.

While some investors do get embarrassed when Wilhelmsen is pitching his male masturbator, when he talks about it like it’s the most natural thing in the world, they also feel more comfortable talking about it, he says.

“It opens up investors' curiosity, because it's a subject that everyone wants to talk about — it’s just they believe they’re not allowed to do so.”

“We’ve become very immune to investor awkwardness,” says Kabir. “Words like ‘condom’ and ‘vagina’ come out very easily during pitches and we take pride in that.”

Investors tend to respond well to the openness, but it’s also made it easier to root out those who aren’t right for Hanx, she adds. “If they’re the type to shy away from [talking openly about sex] we know they’re not the right investor.”

Other roadblocks

Fundraising isn’t the only challenge facing sextech startups.

For many in the space, advertising in the same channels as other consumer brands can be tricky. All the major social media sites and app stores have content moderation policies that prevent brands promoting or selling products related to sex on the platforms.

“There is no replacement for direct digital advertising on these platforms,” says Jackie Rotman, founder of femtech advertising non-profit group the Center for Intimacy Justice. “Until we have alternatives to these platforms, [health and wellness startups] are never going to be able to access the hockey-stick growth that’s enabled by digital advertising.”

There are signs things are changing, says founder and CEO of Kama, Chloe Macintosh. Six months ago, platforms like Apple and Google relaxed their policies on not promoting anything to do with sex on their app stores.

“Usually terms related to sex don’t rank well when searching [on app stores], and the change in policy has created a lot more organic traffic. We get thousands of extra downloads a day just because of that,” she tells Sifted.

Despite that, most sextech founders still face huge barriers when it comes to promoting their products, and even business fundamentals like payment processing aren’t always straightforward.

Within two days of launching, Hanx’s payment provider refused to process its transactions because it classified the startup as “adult”.

“It refunded all transactions from our very first customers — it was a major blow," says Kabir, who had to scramble to find another payment provider. "It just makes it incredibly challenging to grow and build your business when you have these roadblocks."

But these challenges create exceptional founders, says Schofield. “They often become the best marketers because they've had to think outside the box of Facebook or Instagram. Or they’re great at working out their manufacturing supply chain because they face prejudice in certain areas.”