Within hours of Klarna announcing its $10.65bn valuation last week, investors rushed to defend its new crown as the 4th most highly-valued private fintech in the world.

Hans Otterling, partner at the VC Northzone, told the Swedish press that this was positively a bargain compared to fintechs like Paypal or AfterPay, given how fast Klarna — which allows consumers to pay for goods in instalments — is growing. “I would say that it is actually a low valuation of the company," he said.

The rights and wrongs of private valuations can, of course, be debated endlessly. But Klarna has said it plans to float on the public stock exchange in the next 1-2 years, meaning its chunky price-tag will soon be put to the test.

So what does the Swedish fintech need to do to justify its ~$11bn valuation to public investors? And can it lay a successful path for other European fintechs that are hoping to list publicly one day?

Here are the headwinds and tailwinds facing Klarna on its route to an initial public offering (IPO).

Exponential growth

Listing as a tech company can be humbling.

In particular, there’s huge pressure on tech startups to show ‘hockey-stick’ growth ahead of an IPO, says Harry Briggs, a fintech partner at OMERS Ventures.

“As a rule of thumb as a public tech company, you want yearly revenue growth to be at 20%, ideally 25%,” he says.

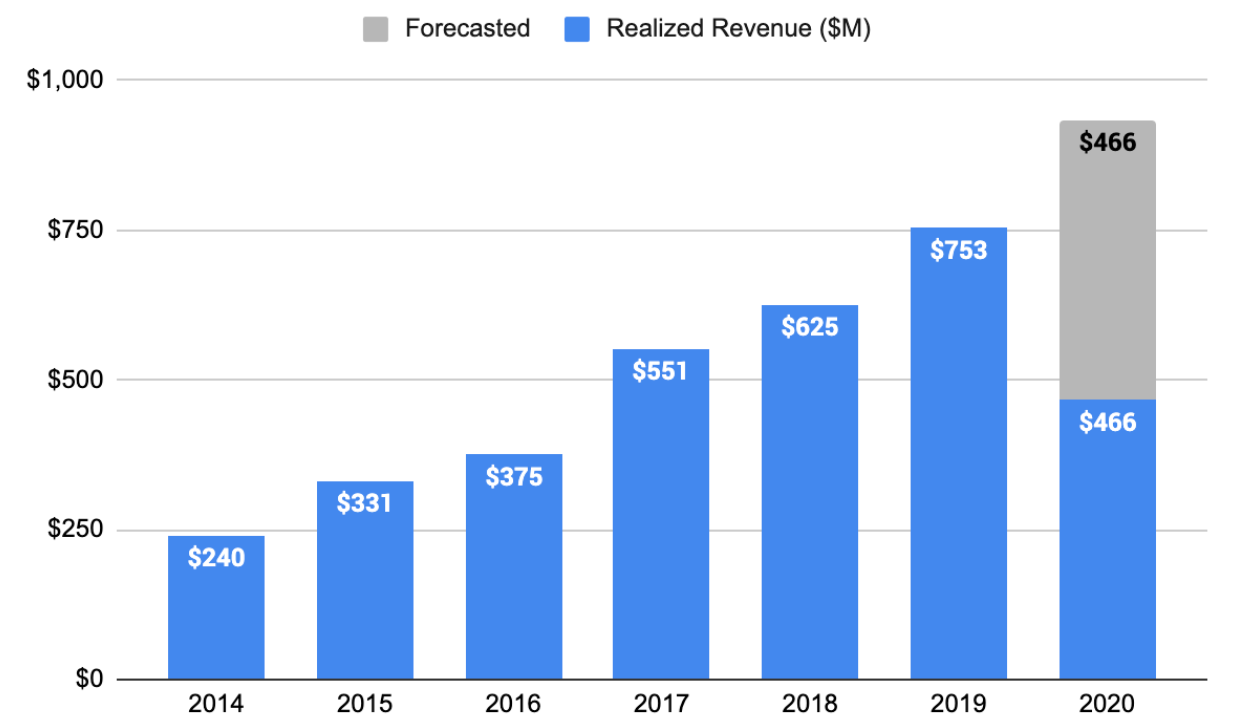

Klarna’s latest figures (printed below) suggest it will need to produce a few winning years to pull off the kind of valuation it wants, going by Briggs’ benchmark.

Briggs notes: “They’re clearly very impressive [numbers]...but in 2016, they barely grew. Then again in 2018."

Its most recent figures suggest it's moving in the right direction, however. The first half of 2020 showed a 36% increase in revenue versus the first half of 2019, thanks to the 'Corona-effect'. Meanwhile, Klarna app downloads are up 95% year-on-year across the US, Sweden, Germany and UK, according to data from App Annie. The company also reportedly brings on 200 new retail clients every day.

Augmentum’s Tim Levene agrees that growth numbers are looking good, but argues Klarna has to continue this streak to justify a valuation that’s 10 times its revenue. “You’ve really got to believe there’s a big growth story there to pay that price,” he says.

Levene added that key questions to consider ahead of an IPO include:

- If you take away marketing, what’s Klarna's underlying profitability?

- Are older markets like Germany and Sweden still growing?

- What’s the recurring revenue from existing customers?”

- Will there be broad consumer adoption of 'buy now pay later' schemes?

- Can Klarna crack the US?

Still, one factor working in Klarna’s favour regarding its valuation is that it has not issued any preference shares, including in the last round.

That means investors have not paid for priority in the event of an exit in exchange for a kinder valuation. In other words, they genuinely believe it’s worth at least $10.65bn.

👉 Read: Klarna's valuation history: explained

Consumer change

Klarna’s fate is partly dependent on a continued cultural embrace of “buy now pay later” (BNPL) products.

The company — and its competitors such as AfterPay and Zip — allows shoppers to pay for products later in the month or in instalments, effectively giving them an interest-free loan.

This is proven to boost consumer spending and in return, Klarna charges its 200,000 merchants around the world, such as Asos or H&M, everytime it is used as a payment option.

At the moment, consumers and merchants seem to be on board with BNPL. Indeed, Klarna has seen sales surge during lockdown as more people shop online in what could be a long-term trend, and now counts 90m users across 20 countries.

Meanwhile, shares in listed BNPL firms like AfterPay, Zip, and Settle have soared in recent months after an initial dip in March.

Another sign this space is booming is the fact major operators like PayPal and Amex have all launched ‘instalment’ payment features.

“You can see someone like Paypal buying Klarna [after an IPO],” Briggs tells Sifted, explaining this would provide a natural boost to its stock-price.

Major fintechs like Alibaba and Tencent are also betting on this sector’s rise, having invested in AfterPay (valued at ~A$25bn) earlier this year, while Ant invested in Klarna in March.

“It basically gives investors exposure to lending but at lower risk, arguably,” explains Tim Levene. “The lifecycle of each loan is short, eg. 30 days, so you can tighten credit-controls quickly when you see risk coming.”

Indeed, Klarna recently reported that less 1% of its borrowers defaulted during lockdown, which is rather impressive (Note: the company has granted late-extensions on its loans, so further defaults could still come down the line).

Additional BNPL copycats also keep joining the fray, including France’s Alma, New Zealand’s Laybuy, and London-based Divido, which creates software for banks to offer split-payments to their users directly.

Nonetheless, BNPL is still a relatively new concept for shoppers, particularly in the UK and the US, and has not been without friction.

There have also been frequent headlines about young people getting into debt using the service, buying more than they can afford (albeit usually capped at ~£600). This has also been followed by repeated threats by European regulators to crack down on BNPL companies, which could pose an existential threat to Klarna's core business.

Notably, Sifted calculated that up to one-third of Klarna's revenues likely came from late-fees and interest from consumers in 2019, proving there is often a direct cost to users.

Cracking the US

One fundamental part of Klarna’s growth strategy is cracking the US market. Yet the jury is still out on whether or not it will.

Klarna first planted its flagpole in the US in the spring of 2015, hoping to add a giant new market of consumers and retail-partnerships to its ranks. But it’s seen a series of hiccups in the years since, including a massive series of layoffs in 2017.

Expansion into the US has also proven a drain on its financials, landing Klarna in the red for the first time in its history, according to the company’s 2019 annual report.

Part of the issue is that defaults in the US are higher, suggesting finding reliable borrowers has been harder there.

Having said that, the US-mission is slowly starting to look more positive. After investing much of its $460m fundraise last year into the US, Klarna reported it had surpassed 9m US sign-ups this summer. This constitutes around 10% of its total user-base.

The company’s chief executive Sebastian Siemiatkowski also told Sifted “it is likely the US will soon be our largest market."

He also noted that overall losses there are decreasing, with transactions growing by 44% year-on-year.

Indeed, if Klarna can make it in the US, it will add serious credibility to its valuation, Levene remarks.

“Cracking the US would be a feat that few others [from Europe] have done.”