They say technology can bring people closer. But we are now moving to an era of tech designed to keep us apart.

The wearable device around your neck buzzes to warn you that you have got too close to your co-worker. A box in the corner of the office monitors your breathing rate, watching for signs of Covid-19 breathlessness. After work, you join a “virtual queue” using your mobile phone to book a timeslot to visit a museum or your local pub.

It’s not a distant vision of the future — all these technologies are being developed now and could be coming to your workplace soon, as countries begin to ease Covid-19 restrictions and try to work out how to manage a low-contact post-pandemic society.

Not Bumping

As early a Monday a number of UK companies will start testing a wearable device called Bump, which will warn employees if they come closer than the government-mandated distance of 2m from each other. It is one of the technologies that could help companies restart operations while making sure that employees keep safe.

“We’ve had interest from manufacturing, food, logistics, retail and construction companies,” says Brian Palmer, chief executive of Tharsus, the UK advanced robotics company that makes the device. There are even two schools that will test the system. “We wanted to maximise the feedback from as many different environments as possible.”

This is a bit like a submarine sonar system — it pings signals at people to very accurately locate where they are.

The Bump system uses radio frequency signals to measure how close someone is, much more accurately than the bluetooth signals that many mobile phone-based contact-tracing systems are relying on to record who people have been near.

“Bluetooth doesn’t actually measure distance very accurately,” says Palmer. “This is a bit like a submarine sonar system — it uses bluetooth to initially sense if someone is nearby and then it pings signals at them with increasing frequency to very accurately locate where they are.”

The idea is that the Bump warnings will gradually teach people what a two-metre distance looks like and where the safe places are to walk and stand when at work. Data of the day’s interactions can be downloaded by both the employee and employer to make sure no one has put themselves at risk.

Tharsus, which is usually best known for making the robots that whizz around Ocado warehouses, has tested the system on its own premises and says the requirements of social distancing can come as something of a surprise.

“Two metres is quite a long way — most people don’t realise. And people have very different perceptions of distance,” says Palmer.

At £100 per device, it will not be cheap to kit out an entire workforce with Bumps. Palmer says some companies have found the price too steep, but others have taken the view that, if it allows them to begin operating again, the price of the device will be paid back in half a shift.

If the initial beta tests go well, Tharsus says it could be shipping devices in the tens of thousands by mid-June.

Counting every breath

Monitoring people for signs of illness is likely to become another part of the daily routine.

In many Asian cities, people have their temperature taken on entry into offices and public places. But, taking temperatures may not be enough. Many people who fall ill with Covid-19 never develop a fever at all.

Monitoring breathing might actually be a more accurate way of spotting someone with the disease, says Alexander Giles, chief commercial officer at Iceni Labs, a privately-owned, UK-based engineering company.

A technology that Iceni Labs originally developed for the British Ministry of Defence could have a surprising second use in helping control the pandemic.

The clever bit is an algorithm trained to identify distinctly human breathing patterns.

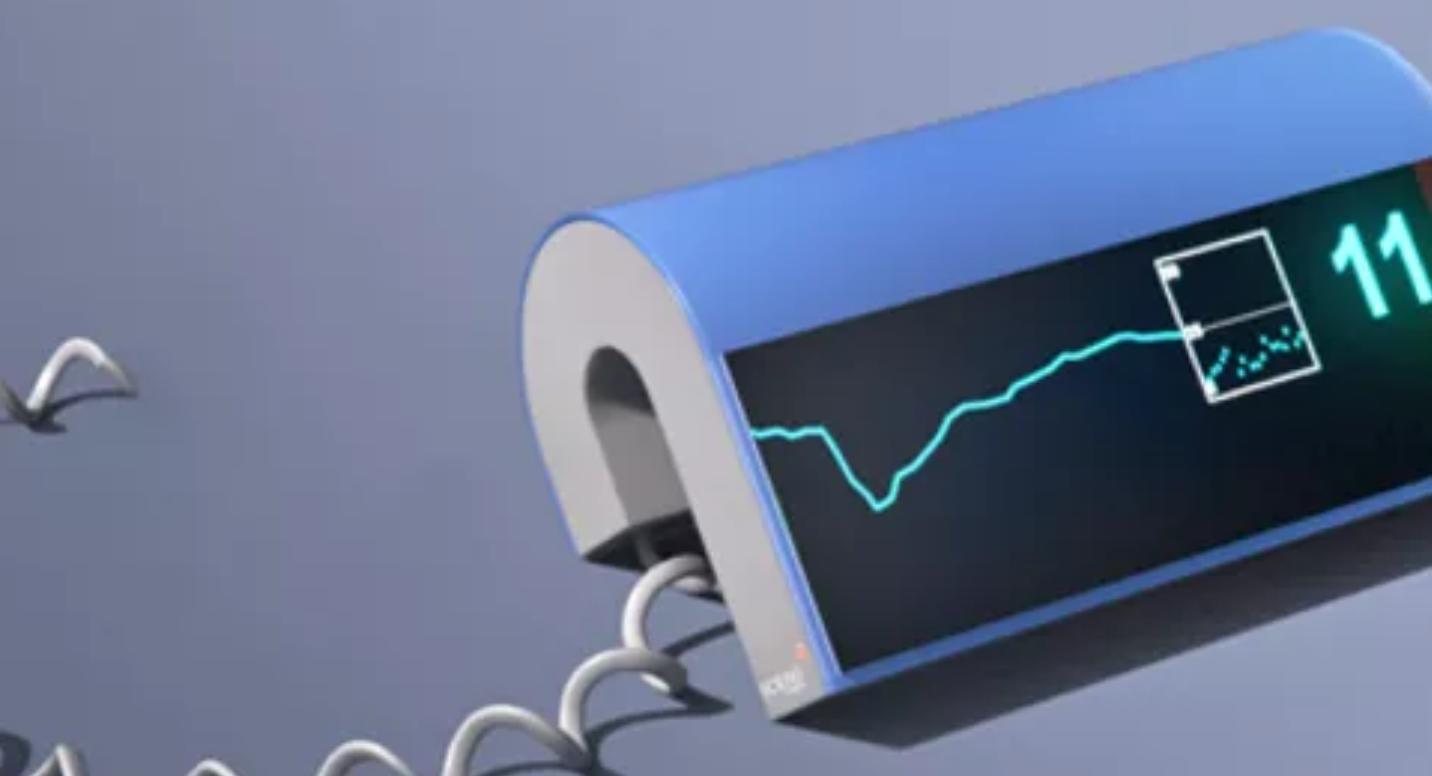

Iceni’s device uses ultra-wideband radar to detect the presence of humans — handy, for example, if you want to know how many enemy soldiers might be hiding behind a wall in a combat zone.

Using radar to detect movement is not new. The clever bit is an algorithm trained to specifically identify a human — as opposed to a dog, or a rotating desk fan — by recognising distinctly human breathing patterns (humans generally take around 12-16 breaths a minute compared to some 15-60 for dogs, for example).

Even before the Covid-19 crisis, Iceni were looking at the possibilities of using the technology for medical as well as military applications. The team had just completed a 12-month clinical trial with the sleep apnea clinic at the UK’s Royal Papworth Hospital. The trials confirmed that the monitor could track differences in breathing down to an accuracy of a quarter of a breath per minute.

Which makes it potentially perfect for detecting the sudden breathlessness characteristic of Covid-19 cases. Initial use will be in hospitals where there is currently no way to systematically measure breathing rate accurately. You can measure patients' heart rate, temperature and blood pressure with machines but, says Giles, outside of intensive care units, measuring breathing rates usually involves someone watching and counting manually.

The only way to get back to normality is to monitor people. We may need a layered approach... monitoring someone’s breathing while they are having their temperature checked.

Giles says the device — which can be placed on a wall or under a bed and involves no contact with the patient — could be used to spot patients whose breathing suddenly worsens.

Iceni received funding from UK Research and Innovation, the government funding body, last month to run a trial to collect data from Covid-19 patients. “We are beginning to see that breathing changes a lot sooner than we thought in these cases. If we were monitoring people’s breathing, a change from the trend line would alert medical teams far sooner to problems,” says Giles.

Beyond hospital use, he says the breathing monitors — expected to sell for around £2,000 each — could be used in offices and places like airports, alongside temperature monitors.

“The harsh reality is that we are likely to have a second spike of Covid-19 before the end of the year. The only way to get back to normality is to monitor people. We’ll need to be monitoring certain segments for two to three years,” he says.

“We may need a layered approach. A system like ours could be monitoring someone’s breathing while they are having their temperature checked.”

Virtual queues

Virtual queuing is already familiar to visitors to theme parks. UK-based Accesso has for years provided “speedy passes” for visitors to places like Legoland, which allow them to book specific slots on different rides, eliminating the need to stand in long queues.

A lot of businesses are looking for technology that will help them reopen. One of the big problems is managing queues when you can only let a few people in at one time.

The AIM-listed company’s fortunes have been mixed recently, with the share price sharply down since the end of 2018. But the pandemic may — bizarrely — provide a boost for the company. While it may have lost business while theme parks and attraction are shut, it has also started to see interest in virtual queue management from a whole new set of customers

“There have been inquiries from industries that I never would have thought we would be dealing with,” says Steve Brown, the company’s chief executive. “A lot of businesses are looking for technology that will help them reopen. One of the big problems is managing queues when you can only let a few people in at one time.

“In a small venue, you could handle it with a manual solution, handing out paper tickets or drawing boxes on the floor. But in big stores — or places like airports — you have multiple queues at once and a tech solution becomes more necessary.”

Brown is hoping that what might start as a necessary Covid-19 response would become a permanent feature.

“If we install this for social distancing, venues won’t easily be able to go back. Once customers get used to the convenience they will expect it always.”