Once a far-fetched fantasy, biomanufacturing — reprogramming or genetically turbocharging organisms to produce outputs to fight disease, boost food production or gobble up carbon dioxide — is growing and growing.

Biomanufacturing, the focus of Sifted’s latest Pro briefing, holds the potential to unlock up to $4tn a year over the next 10-20 years, according to consultants at McKinsey.

But there’s a catch. With startups having made strides in the genetic design of novel foods and products, they’re now waking up to the reality of having to manufacture them at scale — and there's a dawning realisation that the sector has sleepwalked into a capacity crunch.

“Designing new products is no longer the bottleneck — it’s scaling them,” says Tess van Stekelenburg, a biotech-focused investor at Hummingbird Ventures.

The global operating capacity of bioreactors — the stainless steel tanks that companies need for large-scale production — stands at 61m litres, only 10m of which is unreserved for use. By 2030, as much as 10bn litres of capacity will be needed just for new creations in the food sector, according to consulting firm BCG.

Faced with that vat drought, a growing cohort of startups is rising to the challenge and developing new types of bioreactors. They’re hoping to help other startups produce novel food, fibres and cosmetic ingredients more cheaply and efficiently, and prove that biomanufacturing can cross the threshold from lab to market.

From lab to scale

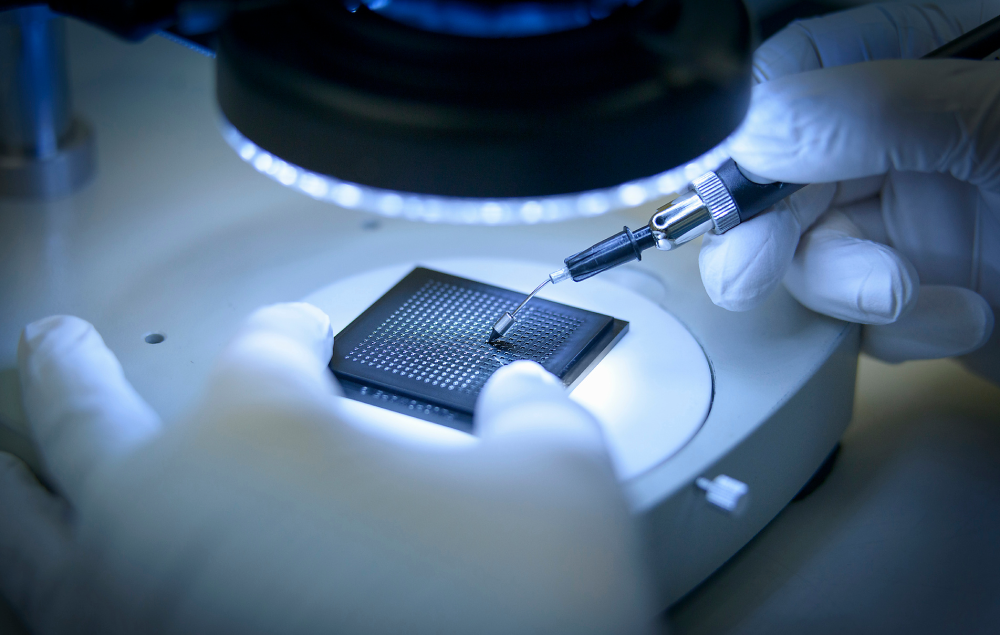

Companies building bioreactors are split into those making tanks for fermentation — the process by which raw materials are transformed into new consumables by microorganisms like yeast and bacteria — and those for growing new products from cell cultures.

Startups in the first category include Switzerland’s Planetary and Netherlands-based DAB.bio. The second group is made up of a handful of UK startups — Extracellular, Cellular Agriculture, Unicorn Biotechnologies, Trisk Bio and Animal Alternative Technologies — as well as Germany-based Innocent Meat. Germany’s The Cultivated B. is operating across both categories.

Then there are those who are developing food products and their own bioreactors, like Czech Republic-based Bene Meat and Germany’s Keen4Greens.

It’s a new gold rush, and we’re the ones making the shovels

The emergence of all these startups is partly down to the widening remit of biomanufacturing itself. Initially confined to healthcare, more than half of all bio-activity is now estimated to be in other areas including agriculture and consumer industries.

“It’s a new gold rush, and we’re the ones making the shovels,” says Hamid Noori, managing director of The Cultivated B., which will manufacture bioreactors to sell rather than operate them on behalf of others.

Many bioreactor-focused companies target novel food companies as customers. “There are now many heavily funded companies in this space who have nowhere to go to grow these products at scale,” explains David Brandes, cofounder of Planetary.

Whether they’re producing bioreactors to ship to others or operating them themselves, these companies address two pain points for startups designing bio-based products. They help validate their technology at scale and drive down costs — 90% of technologies in synthetic biology fail because they can’t be scaled past the lab stage.

“A lot of times a strain you’ve cultivated will perform well and produce biological products at small flask scales, but the second you put it into a larger reactor, entirely different dynamics are at play,” explains van Stekelenburg.

The problem is that companies lack data on the reasons behind failures, making the process lengthy and expensive.

And that’s for those who are lucky enough to find partners for the scaling process in the first place, where waiting lists are pervasive. Laura Turner, an investor at London-listed cellular agriculture VC Agronomics, says she has seen companies wait for 18 months to get bioreactors in-house.

From scale to market

Similar bottlenecks exist when it comes to producing at commercial scale. “We just don’t have bioreactors purpose-built for biomanufacturing,” says van Stekelenburg. Most existing facilities in Europe were developed several decades ago for industries like chemicals or beer brewing.

Commercial-scale facilities will be critical to decrease the cost of companies’ end products and allow them to make a real dent in purchasing habits.

Exactly how to achieve this is still up for debate. Brandes argues that in the food sector, “production capabilities have to be scaled up — not out — for the unit economics to make sense”. In his view, instead of spreading production across smaller reactors, companies need to work with a production capacity of at least 250k litres.

Planetary’s first commercial-scale facility, set to open in Switzerland in 2024, will operate a total capacity of 500k litres.

Noori, who’s taking a more small-scale approach, thinks that such large-scale production is a bad idea. “If the medium inside a huge tank spoils, you suddenly lose millions of dollars in value. It’s better to distribute that risk across several smaller reactors.”

The Cultivated B. will instead produce bioreactors with a capacity of 25k litres. It plans to produce 100-250 a year once its first manufacturing facility opens next year.

In Noori’s view, savings won't be determined by the size of bioreactors but by innovations in the reuse of raw materials needed for the bioprocesses.

For products grown from cell cultures, growth cultures remain a costly bottleneck. “You can’t just look at the price of a reactor — the most expensive thing is what you put into it, and this is only going to get more expensive as technologies mature,” says Noori.

Going it alone

Faced with a shortage of bioreactors, some startups have taken to building their own “out of desperation", says Turner, who sees startups spending money on expensive physical assets as a poor use of equity funding.

To support portfolio companies scaling up, Agronomics has instead founded its own company, US-based Liberation Labs, to operate commercial-scale bioreactors for precision fermentation. Construction of the 600k-litre facility will cost $65m.

But bioreactors aren’t just expensive. It’s also hard for startups to find the talent they need.

There actually aren’t a lot of people around the world who know how to do this

Part of the problem comes down to different worlds colliding. “Most biomanufacturing companies were founded by biologists or geneticists, who are now realising they need the expertise and skillsets of process engineers,” explains van Stekelenburg.

It’s also an industry where it’s lonely at the top — building production facilities for giant bioreactors for entirely new industries isn’t exactly a mainstream gig. “There actually aren’t a lot of people around the world who know how to do this,” says Turner.

Things appear more manageable at a smaller scale. Colorifix, a UK startup that engineers and manufactures natural pigments for textile makers, built its own 300-litre bioreactors which have since become a separate product line for the company.

“Commercially available bioreactors are far too expensive and not suited to work in our environments. Better safety and turn-around time and a smaller carbon footprint were also all compelling reasons,” explains cofounder James Ajioka.

An uncertain future

If bioreactor companies focus primarily on building out capacity, it’s unclear how they'll escape the risk of commoditisation.

Integrating a tech component into startups’ hardware will be critical to ensure they make a suitable VC investment. “Over time, if you want to build scalable infrastructure in this space, there needs to be long-term technological lock-in, otherwise it makes more sense for startups to scale with project financing [rather than equity financing],” argues van Stekelenberg.

The high-capex (capital expenditure) nature of the business also makes bioreactor companies particularly vulnerable in a souring economy. Most companies in the sector aren’t purely financed by VCs but rely on debt to construct their facilities, meaning they're directly exposed to rising interest rates.

And then there’s the huge hike in energy prices in Europe, which together with labour and sugar make up 75% of costs for those bioreactors focused on precision fermentation.

With startups in the food sector already operating on slim margins in the hope of reaching price parity with conventional products, they will be among those worst affected by companies that operate bioreactors passing increasing costs onto their customers.

“Any capacity that was entertained for food production in Europe is now no longer economically viable, because the costs will be too high,” explains Turner. “There is a lot of demand from food companies for them [bioreactor contract manufacturers], but they will probably have to find more customers in higher-value items.”

Amelie Bahr is a senior intelligence analyst at Sifted.

***

Looking for digestible insights into the biomanufacturing sector? Sifted’s Pro Briefing on the industry will get you up to speed fast on what you need to know. Check out what Pro membership can offer you here.