European investor Draper Esprit is on the hunt – but not just for startups.

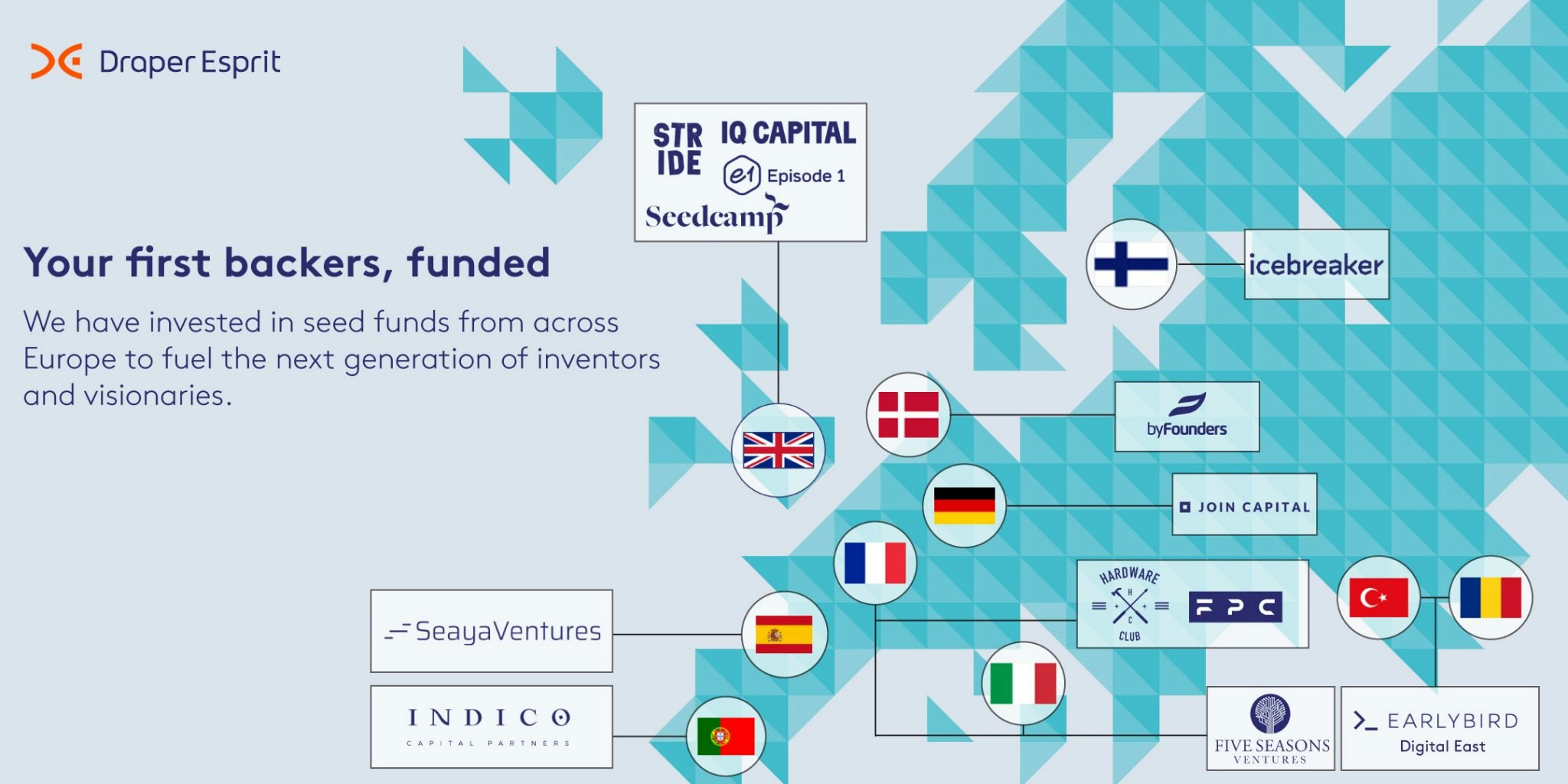

Over the next four years Draper, which counts Revolut, Clue, Graphcore and Trustpilot amongst its portfolio, plans to invest up to £75m in seed funds around Europe.

This is an unconventional move for a venture capital fund – which are usually solely focused on investing directly in companies – but Draper hopes it will give the firm extra reach across the continent.

The 20-year-old firm, which unusually for a VC is publicly listed, has already invested £35m of the £75m in 12 funds, and committed to five more since launching the strategy in late 2017.

Draper is specifically looking for early-stage funds in geographies or sectors where its in-house team don’t have expertise, says Ben Tompkins, managing partner at Draper.

On the shopping list at the moment: gaming, blockchain, industry 4.0, Sweden and Eastern Europe. Current investments range from Nordic seed funds Icebreaker and ByFounders to food tech fund Five Season Ventures, and are generally around €1-3m.

The seed investment stage isn’t so beloved by the institutional investors: early stage means risk.

“We help the seed fund ecosystem either with a first cheque, which usually crystallises further investment, or we help close a fund when it’s almost there – when it has €18m committed out of €20m,” says Jonathan Sibilia, head of fund of funds at Draper. “The seed investment stage isn’t so beloved by the institutional investors: early stage means risk.”

For Draper though, it means opportunity: to bolster Europe’s investment ecosystem, tap into underserved sectors and cities it expects to take off, back fund managers with a track record as “trend spotters”, and give startups it has its eye on a smoother ride through early-stage fundraising.

“Fundraising takes time, time you don’t spend growing your business. If we can be there helping the startups we know and like already, fast tracking the round, that’s a win win,” says Sibilia.

Competition amongst VCs

The strategy is also yet another example of how competition is hotting up for investors, who are increasingly trying out new ways to fill their pipelines with the most promising startups. “10 years ago, VCs sat in their marble halls waiting to entrepreneurs to meet them,” says Tompkins. “It was a lazy industry. Now it’s more competitive and that’s good, it’s good for entrepreneurs.”

10 years ago VC was a lazy industry.

For Draper, which tends to invest £5m-£25m into companies at Series A-C, working closely with seed funds is a way to keep tabs on companies it might later want to invest in and improve its deal flow. These funds, such as Hardware Club, also help Draper run due diligence on investments.

“These guys are experts in anything from e-scooters to internet of things to mobility, and when we are seeing companies with a very prominent tech angle, where we need additional expertise, we can leverage their expertise,” adds Sibilia.

The new El Dorado

Local seed funds are also likely to have a good grasp on smaller ecosystems, which are becoming increasingly exciting, says Tompkins. Stockholm (where we meet) is a good example of the kind of city Draper’s keeping an eye on, he says: “Big companies – like Spotify, iZettle, Klarna – build a tech base, soak up all the talent, change the culture, and then all those people [working for them] want to do their own thing.”

Spain and Portugal (where Draper recently backed Indico, now Portugal’s largest VC firm) could also be the “new El Dorado”, says Sibilia. “We see entrepreneurship growing, and a need for capital.”

Most fund managers can’t do it… but as a publicly-funded VC, we can do what we like.

It’s unlikely, however, that other investors will be following suit. Draper is in a unique position: as a publicly listed company, it has more flexibility over where it invests its money.

“Most fund managers can’t do it,” says Tompkins. Their investors would object to paying a “fee on a fee” – contributing to management costs for both sets of VCs – “but as a publicly-funded VC, we can do what we like.”

This means Draper can also invest significant amounts into seed funds. Where other later-stage funds do invest in seed funds, the amounts are usually far smaller: when investment firm Eden Ventures, where Tompkins was previously a partner, invested £200,000 in seed-stage fund Seedcamp it was “written off as marketing”, he adds.

Sibilia hopes that Draper’s investments into early-stage funds will pay for themselves, and kick off a “never-ending cycle”.

Tompkins is more measured: “It’s unusual – and we haven’t proven the model yet.” But then again, VCs are in the business of backing unproven models.