Orange, E.ON and Santander are the latest in a long list of companies that have spun out their corporate venture arms — this list includes, among the others, BBVA, Siemens, AXA and SAP.

Let's start with a bit of history.

- SAP Ventures was rebranded as Sapphire in 2014 to reinforce its status as a firm independent from the German corporation.

- BBVA spun off its $100m venture arm (BBVA Ventures) into a separate LLC, Propel Ventures in 2016, increasing the fund to $250m.

- In late 2016 Siemens set up a separate VC unit (next47) to foster disruptive ideas more vigorously.

- AV8 Ventures (a €150m fund) was launched in 2019 by Allianz (in parallel to Allianz X, the VC arm of the group).

- In September 2020 Santander spun out its fintech venture arm (Santander InnoVentures first established in 2014) and rebranded into Mouro Capital.

- In October 2020 E.ON launched Future Energy Ventures (a €250m fund), spinning-out the startup investment portfolio of E.ON and Innogy.

- In January 2021 Orange announced the spinoff of its VC arm Orange Ventures.

I see two major corporate venture trends here.

Firstly, separating investment operations from the mothership and creating an independent fund.

Second, removing the visible affiliation with the parent company through rebranding (most of them are 'disguised' CVCs).

Why do companies increasingly want to do this?

There are six possible reasons.

1. Speed and agility

CVCs typically have a longer decision process, sometimes requiring multiple approvals (tiered process) and often being constrained. Being a separate entity allows them to move faster.

Jay Reinemann, Propel Ventures Partner, says: "Captive bank funds have less freedom, less speed.”

"We have true, independent operation when it comes to investment decision making. I think entrepreneurs value speed of decision making from their prospective investors, and we have the same agility that’s possible in a totally independent financial firm," says Chris Barchak, former Venture Partner at next47.

2. Perceived conflict of interest

The fact that spinout CVC funds are renamed something very different from the parent company name suggests that the goal is to reinforce their independent status.

“We did suffer from adverse selection to some extent. There’s a stereotype some VCs hold against corporate investors, and VCs are often gatekeepers to opportunities, so for example you’d hear about a round and the round would already be over”, says Reinemann.

Being independent is supposed to make these funds a more attractive investor, without the perceived conflict of interest that strategic investors typically have. It is too early to say, yet, if they do get more deals as an independent entity.

"Shifting to a separate brand also reduces any potential affiliation that entrepreneurs may fear as potentially conflicting (commercially, IP), further reassured by a cleaner legal separation," says Manuel Silva Martínez, General Partner, Mouro Capital.

3. Compensation

This is not a trivial topic. Adopting VC-like compensation models, with partners earning carried interest inside the corporate boundaries, might create a huge discrepancy in compensation. In some cases initial partners at some CVCs made more money than their CEOs, creating some embarrassment.

4. Physical separation

Many CVC funds are headquartered in Silicon Valley, i.e. closer to the top startup ecosystems and far from the mothership home turf. This tells you something — and can also help with the problems of speed and access to the best deals National Grid, the UK-based utility, is a good example of this. With a CVC unit located in Silicon Valley, they were able to build a portfolio faster than many CVC peers.

"Taking the leap to enable true independence for their CVC is very difficult for most corporations", says Reinemann at Propel Venture Partners.

5. Fundraising

If a CVC fund can be truly independent of its parent company, it might be able to add new LPs to future funds. The opportunity to gather investments from third-party investors is one of the reasons behind the recent decision of Orange to "peel off" its VC arm Orange Ventures.

6. Bolder investment strategy

A fully independent CVC might explore the boundaries by investing from time to time in areas far from the core of the parent company and even in companies perceived as competitors.

"A venture capital affiliated with an industrial player should be a lighthouse for the ‘industry to come’.

Investing in emerging competitors that may reshape the future [or] long-term competitive landscape is just as aligned as any other topic," Manuel Silva Martínez of Mouro Capital commented.

Wrapping up:

Independent CVCs are definitely an interesting model, particularly for investing in early-stage companies.

However, to me, they look as a way to get around the problems CVCs have by giving up their unique differentiator: the opportunity to bring the corporate angle into play post-investment — for example, tapping into its global network of customers and brokering introductions. It's a bit like Superman hiding the 'S' on his jumpsuit…

My two cents here is that I'd rather work to solve the challenges CVCs have than giving up their superpowers. How? That's a subject for another article. But in a nutshell, it means CVCs leveraging their strengths (relationship with the business units via implementation managers), while fixing some bugs (process and compensation).

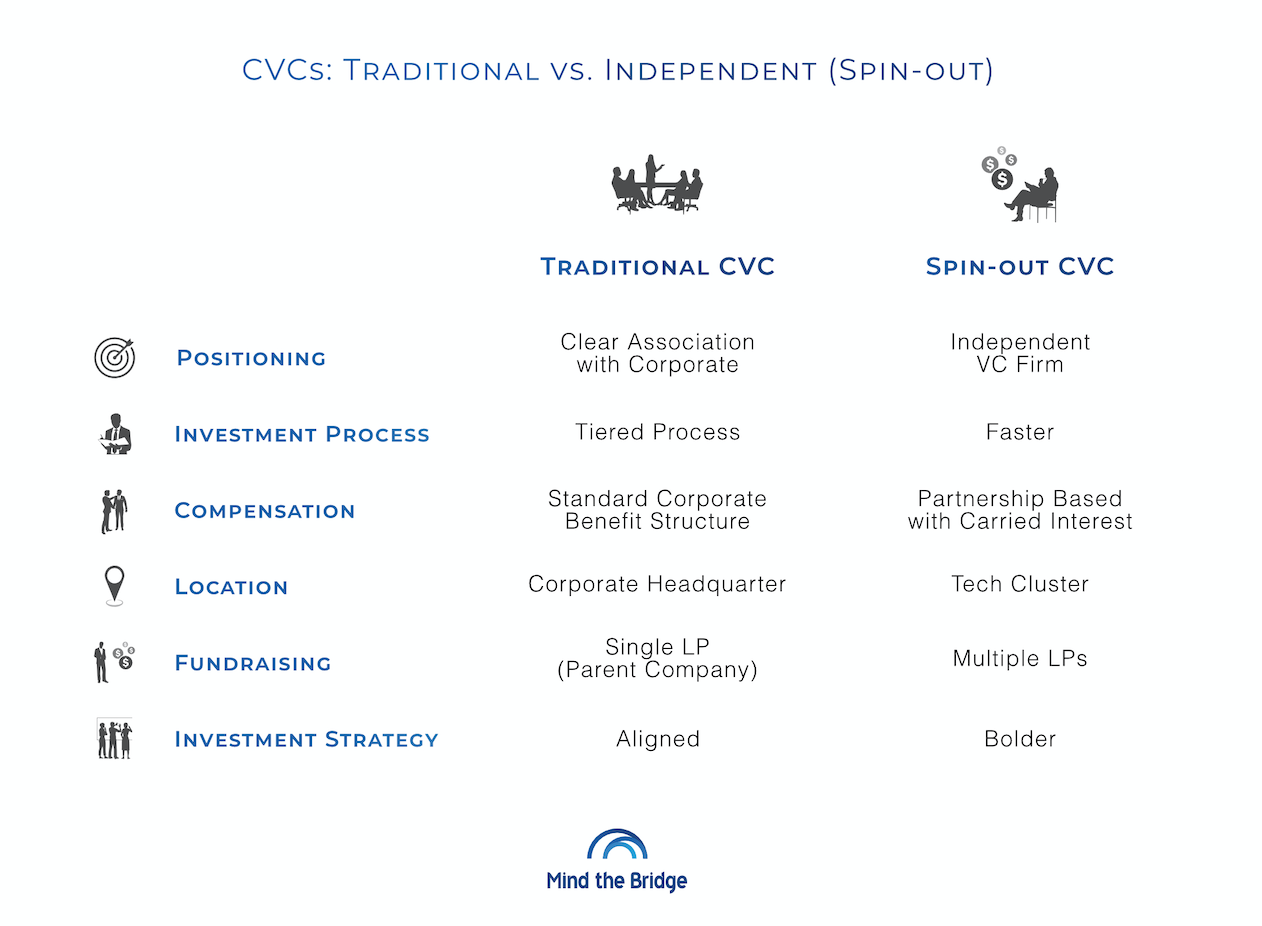

This table summarises the main differences between 'traditional' CVCs and the seemingly 'emerging' model. Please consider that for the latter what we indicate are more possible future directions rather than consolidated characteristics. The jury is still out, like for most of the open innovation trends.